Voices of U of U Health

Research Targets COVID-19

Science is an endless quest. The search for scientific truth never stops. Last winter, when the coronavirus struck, researchers at University of Utah kept on with their work and focused intently on finding better ways to detect, diagnose, treat, and ultimately cure this deadly disease.

The U jump-started COVID-19 research, investing $1.3 million in 56 projects in the early months of the pandemic. The broad range of topics underway include new technologies, drugs, diagnostics, and impacts on health and well-being. U of U Health has published more than 60 research papers regarding COVID-19. Our investigators have been awarded $19 million in grants from outside funding sources for coronavirus research. Some research is based in health sciences labs, while some is based on the main campus. And some research involves interdisciplinary teams from both. One U is not just an idea, it actually describes a thriving combination of dedicated scientists, scholars, and students advancing knowledge.

Connection to Blood Clotting

U of U Health scientists found that COVID-19 causes “hyperactivity” in blood-clotting cells. The changes in blood platelets triggered by COVID-19 could contribute to the onset of heart attacks, strokes, and other serious complications in some patients who have the disease. The researchers found that inflammatory proteins produced during infection significantly alter the function of platelets, making them “hyperactive” and more prone to form dangerous and potentially deadly blood clots. Robert A. Campbell, PhD, senior author of the study and assistant professor of Internal Medicine, reports that a better understanding of the underlying causes of platelet changes could possibly lead to treatments that prevent them from happening in COVID-19 patients. Their report appears in Blood, an American Society of Hematology journal.

Coronavirus in Sewage

One example of One U providing extra capacity and agility for research is a study monitoring samples of municipal wastewater for signs of COVID-19. It is a joint project started by the School of Medicine and the College of Engineering. Jennifer Weidhass, PhD, assistant professor in Civil and Environmental Engineering, leads the study along with Jim Vanderslice, PhD, associate professor in Family & Preventive Medicine. Researchers suspected that wastewater contained valuable clues that might help identify communities where coronavirus infections are starting to appear. They were right. By monitoring the presence of the virus in sewage, local health officials would be able to recommend behavior changes—masking and social distancing—to slow the spread of COVID-19. Results of a two-week pilot program in Salt Lake City were presented to the state and then funded a larger pilot study looking at 10 facilities across Utah, covering about 36 percent of the population. Weidhass and Vanderslice detected more interesting trends regarding early signs of coronavirus outbreaks. The state is now funding a study of 40 facilities in Utah, covering about 80 percent of the population, in partnership with BYU, Utah State University, Utah Department of Environmental Quality, and the Utah Department of Health.

Building a Biobank

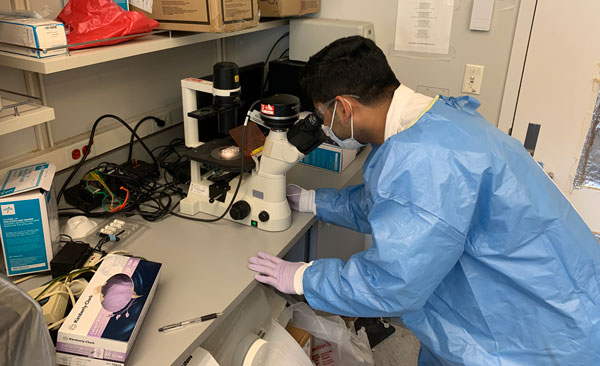

And then there’s a COVID-19 research project that’s building a “biobank” to serve as a foundation for countless other research studies. Elizabeth Middleton, MD, and Adam Spivak, MD, are lead investigators of the patient-centered project documenting how COVID-19 is affecting patients at different stages of infection and recovery.

Middleton is assistant professor of Internal Medicine and Spivak is assistant professor of Internal Medicine. He, along with Rachel Hess, professor of Population Health Sciences and Internal Medicine, are leading a clinical trial testing the efficacy of the drug hydroxychloroquine on mild COVID-19 in patients who are recovering at home. As a part of this trial, they collect patient samples. They are also providing samples to the biobank for use by others. This repository of COVID-infected tissue and accompanying patient data is one of very few in the nation.

The months-long effort will help us learn more about the trajectory of this disease and maybe answer a number of pressing questions, including why certain people are more likely to be infected and why their bodies respond to the infection the way they do? Also, why does a viral pandemic like COVID-19 disproportionately affect minority populations, and what can we do to reduce their risk?

Projects of this scope could only be undertaken because researchers are talented, agile, and collaborative. Their commitment to excellence and willingness to team up with colleagues across the basic and clinical sciences, and across campus, are hallmarks of our collaborative culture and a source of pride for University of Utah Health.