What constitutes high-value health care? That depends on who you ask. In order to provide it, though, it’s crucial that everybody agree on a definition. Otherwise, some stakeholders will be left disappointed. That’s why University of Utah Health conducted the Value Survey: to see how consumers, providers, and employers think and talk about health care in hopes we can find common ground. Dr. Richard Orlandi, U of U Health’s Chief Medical Officer of Ambulatory Health, helps us explore the disconnect.

Interview Transcript

Interviewer: What constitutes high-value health care? That depends on who you ask. In order to provide it, though, it’s crucial that everybody agree. Otherwise, there’s a chance somebody’s going to be disappointed. That’s why University of Utah Health conducted the Value Survey: to see how consumers, providers, and employers think and talk about health care in hopes we can find common ground.

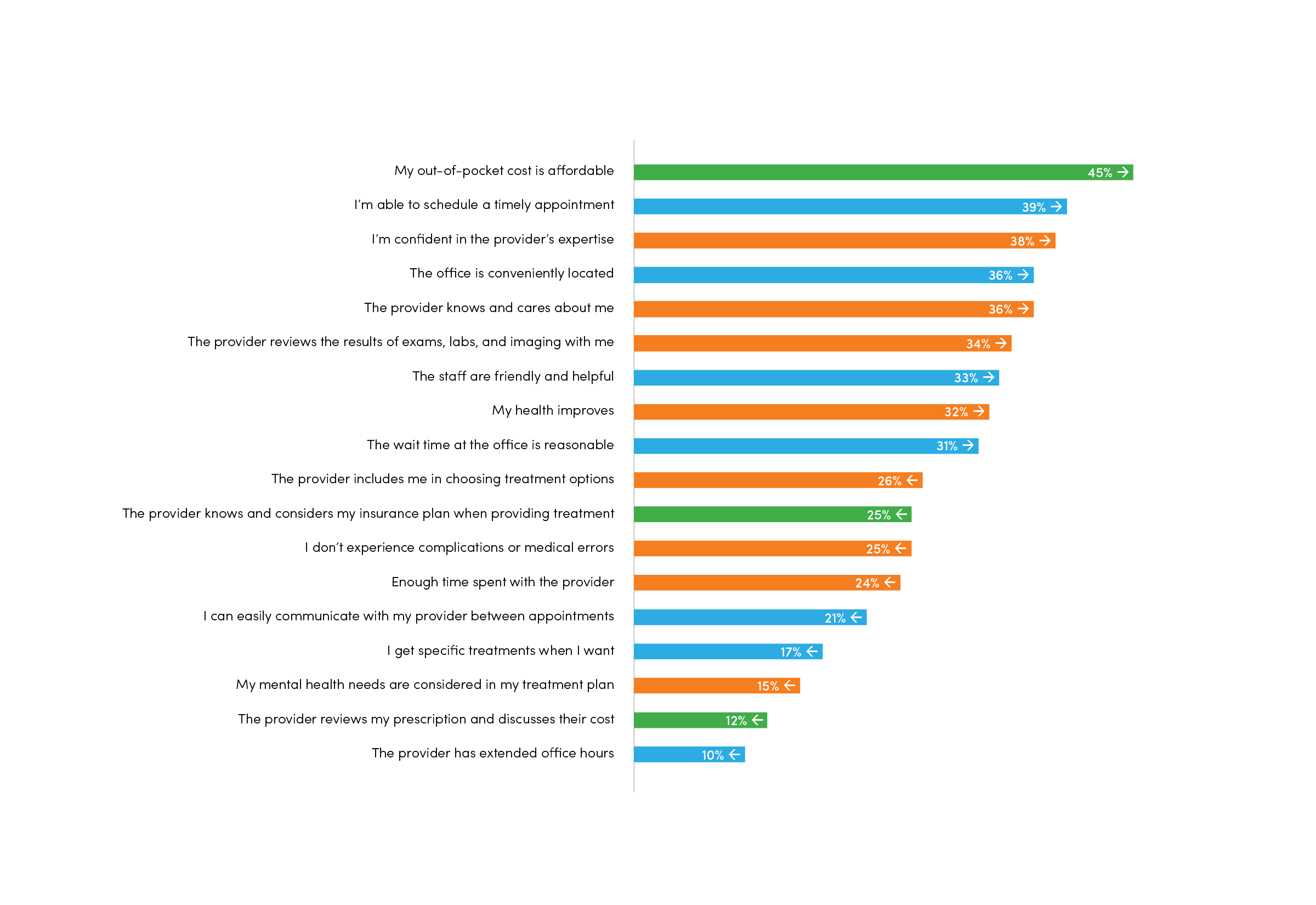

Exploring that disconnect reveals yawning gaps. A majority of patients said cost was most important to them. When asked what value statements they prioritized most,

45% said that their out-of-pocket costs were affordable

The second most commonly selected statement was

39% said they’re able to schedule a timely appointment

In fact, the office being conveniently located and the staff being friendly were more commonly selected as indicators of high-value health care than the patient’s health actually improving. We wanted to explore that more from the perspective of a physician, so we sat down with Dr. Richard Orlandi, U of U Health’s Chief Medical Officer of Ambulatory Health and one of only three fellowship-trained nasal and sinus specialists in the Intermountain West.

Interviewer: What are the best indicators of high-value health care?

Dr. Orlandi: When I think of high value, it’s making sure that patient gets better—that their pain and suffering is relieved. That’s why we all went into medicine. Obviously cost plays a large part in that, but as physicians we’re not necessarily thinking of that at every moment. Sometimes it’s even a secondary consideration.

Interviewer: Is the disconnect between patients and physicians a problem?

Dr. Orlandi: There is a sensitivity around this—and a lot of different ways we can slice it. I was surprised at the degree to which there is a disconnect. Sometimes, as health care providers, we’re not necessarily thinking the same thing the patient is thinking. When there’s that disconnect, we may not be giving them what they want and what they’re expecting.

Interviewer: How have physicians taken this information?

Dr. Orlandi: It’s hard to hear this. Let’s be really honest: you spend the better part of your early life training to be able to do something, and for the survey to say—at least on the surface—that that doesn’t matter really hurts. But if we dig a layer deeper than that, let’s look at it from the patient’s perspective. When I take my car to a mechanic, I have no idea what that mechanic’s abilities are, except for what I hear word of mouth. But I expect that if I have an oil leak, I’m going to be able to get it fixed. Physicians don’t want to hear this, but patients may look at us the same way. I want to get my gall bladder taken out and I don’t want a lot of pain or complications. Well, that’s sort of a baseline expectation. Then it becomes, “How can I do it most conveniently and at the lowest out-of-pocket cost?” If we put ourselves in the patient’s shoes, that seems pretty reasonable. The difficulty becomes, if I take the gall bladder out better than somebody else—or, in my case, do the sinus surgery better than somebody else—but the patient can’t perceive that, I don’t want to hear it. And I think that’s what patients and their employers are telling us in this survey.

Interviewer: Is that something that physicians are just going to have to deal with as we move forward into a different time in health care when convenience and cost are going to start playing into the equation?

Dr. Orlandi: I think we may be seeing a ceiling effect, where patients are not able to spend more for a perception of quality. If we can define and prove that quality, then I think people will pay extra—or be willing to go to a health plan where that’s available. But when we as academic medical centers cannot prove that difference, can we really blame people for choosing a lower-cost alternative?

Interviewer: Some of these disconnects—say, around extended office hours—are pretty easy to achieve.

Dr. Orlandi: We should be able to figure that out, although there is a lot that goes into that. There’s a natural hesitancy on a physician’s part to take time away from his or her family; they may think, “Gosh, I spent all my 20s and early 30s doing that—now you’re going to ask me to do that for the rest of my career?” Really, it comes down to the patient’s perception. If they feel that everything else is equal, why wouldn’t they look for health care that has a lower cost or more convenient office hours? We certainly see that in the younger population, who may want to go to the urgent care department rather than having an established relationship with a physician. They just want that convenience—get in and get out. If they can get what they need that way, so much the better.

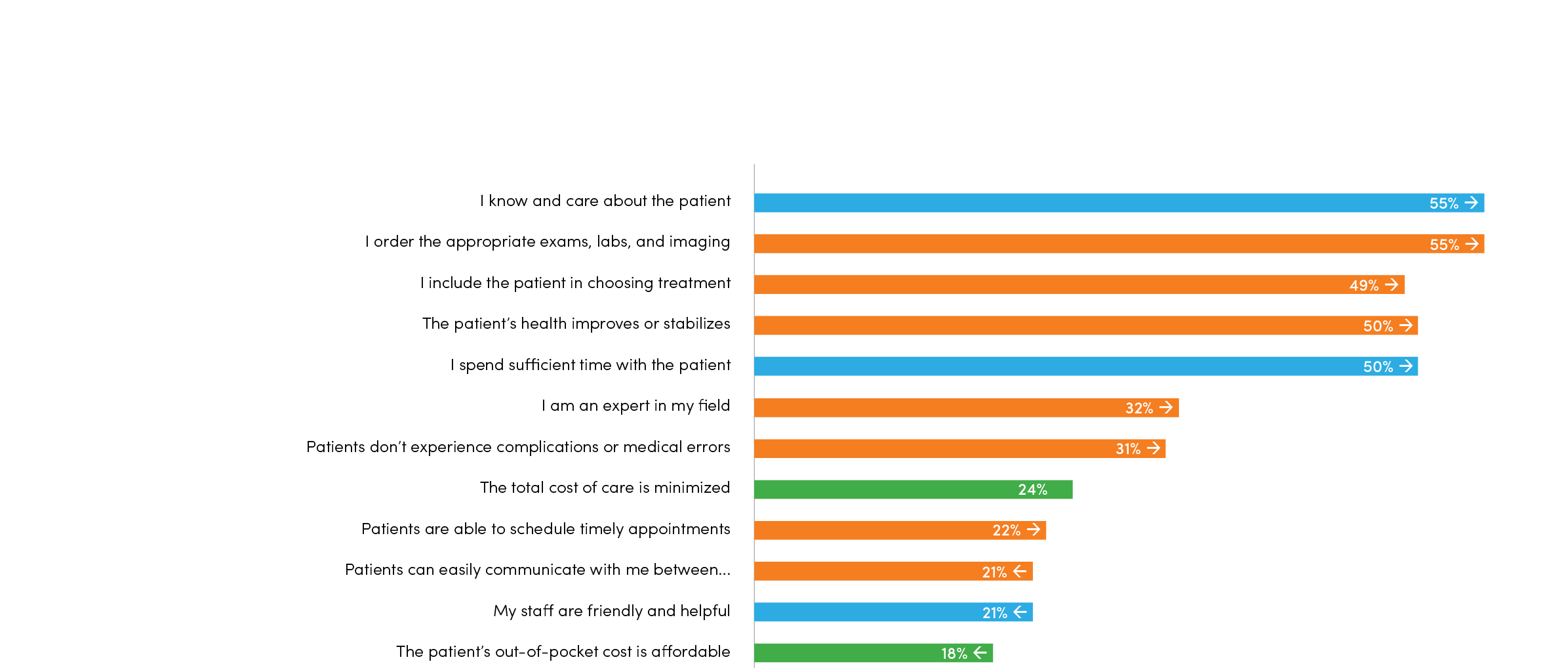

Interviewer: Physicians chose the following statements as most important: “I know and care about the patient.” “I include the patient in choosing the best treatment options.” “I spend sufficient time with the patient.” Those are all very customer service-based, but patients didn’t necessarily rate those very high.

Dr. Orlandi: Again, there’s a disconnect, and it’s possibly because the patients assume that’s already in the baseline. “If that’s present for all physicians, why should I pay extra for it?” The value of that is assumed. Other statements that ranked lower were, “I’m not going to have a complication” and “I’m going to get better.” We’re all patients; of course we value those things! But maybe we just assume that it’s already there. Why would you have to say that’s more valuable? On the other hand, some of the things that physicians said they value I found quite heartening. It’s why we all go into medicine. We want to take care of people, not just diseases. That’s where we derive our value in this line of work. But there are multiple perspectives here, and the more we listen to those multiple perspectives, the more we’re going to be able to come up with a solution that’s satisfactory to everybody.

Interviewer: Let’s talk about cost. Is that the physician’s role, the insurance company’s role, or the patient’s role?

Dr. Orlandi: If we can figure this one out, we’d solve health care [laughs]. Clearly, physicians drive costs in the sense that we order tests and do procedures. Physicians just need to do a better job knowing what those costs are. We know, but not terribly well. We have an order of magnitude sense, but I don’t know that we can partner with a patient and say, “Here are your options. This one will work a little bit better than this one, but it’s going to cost twice as much. Which one do you want?” I don’t know if we have that information and can really involve them in decision-making. I used to poo-poo the idea of putting calories next to a fast food restaurant’s menu— until I saw it and changed what I ordered. Studies have shown that happens, but we don’t factor those questions—“This test, prescription, or procedure costs this much, so do I really need to order it? What’s the plus/minus on that?”—in as much as we need to.

Interviewer: In the survey, 60% of physicians said they thought value would play an important role in transforming health care. Do you have any thoughts on that?

Dr. Orlandi: I do, absolutely. We go back to the value equation, which is quality and service over cost. The outcomes, or quality, are valued more by physicians, while cost and service is valued more by patients and employers. The sensitivity is that we’re experiencing that in different ways. Clearly, the importance of value pervades this discussion. How we weight them from our different vantage points seems to differ tremendously.

Interviewer: How do we bridge that gap?

Dr. Orlandi: There’s the trillion-dollar question. I think we have to better understand one another’s perspectives—and this survey really helps us do that. Again, these results are hard to hear for physicians. No one wants to spend the amount of time, effort, and sacrifice that physicians have to go through to deliver care and then hear that patients think we’re a commodity that’s just being judged based on price. It’s very hard to hear that, yet we need to hear it. We need to understand that our patients are reaching a limit of what they can afford for health care, and we need to be responsive to that.

Interviewer: Do health care systems and physicians need to change to better reflect what consumers want, or do consumers need to change as well?

Dr. Orlandi: I think it’s both. I think we need to be able to have a conversation in a physician’s office where cost is OK to talk about. Right now, it’s somewhat of a taboo subject. We want to talk about health care—we don’t want somebody in our office to talk about what it’s going to cost. Maybe the pharmacist is going to talk about what the prescription’s going to cost, and the scheduler’s going to talk about what the surgery’s going to cost. But what we’re seeing in these survey results is that patients want to have that conversation with the physician. On the flip side, the physician doesn’t necessarily have that information at his or her fingertips. I had surgery a few years ago, and I was shocked when I came in to find out what my co-pay was going to be. No one had had that conversation with me. We need to begin to do that.

Interviewer: What else can we do with this knowledge now?

Dr. Orlandi: Realize there’s a gap and that we’re coming at this from different perspectives because of different experiences. We need to close that gap so we can partner with the patient and the employer on delivering the highest value health care.

Nick McGregor is a Senior Communications Editor at University of Utah Health.