An independent NEJM Catalyst report sponsored by University of Utah Health

SPONSOR PERSPECTIVE

What do physicians want? To know and care about their patients. That is what more than half of physicians said in a national survey sponsored by University of Utah Health exploring what most accurately defines high-value care. Knowing a patient, understanding his or her history, and providing the best advice is one of the most important parts of any clinician’s practice. But as a recent nationwide survey of NEJM Catalyst’s Insights Council found, delivering that kind of thoughtful, compassionate, and expert care every day is challenging under current constraints.

Nearly half of respondents said that the greatest barrier to providing an outstanding patient experience was not enough time with patients. At University of Utah Health, clinical leaders and clinicians often discuss the time squeeze of a clinic visit or a busy inpatient schedule. The data supports this. Spending enough time with the patient was one of physicians’ top five priorities in the U of U Health Value in Health Care Survey. And in this NEJM Insights Council survey, the vast majority of clinicians agreed that it would be worth it to have more time with fewer patients, even if it meant a reduction in their income.

In the minds of many clinicians, the amount of time spent with patients directly correlates to how patients perceive their experience. Patients, however, have a different view. In the U of U Health Value Survey, only one in four patients chose spending enough time with the provider as most important to them when receiving health care. In focus groups and in survey feedback, patients told us they don’t necessarily want to spend more time with their provider — they want to be heard.

Nearly 100% of respondents to this survey agree that listening to the patient voice improves care. Yet recent research published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine found that, on average, clinicians listen to patients for 11 seconds before interrupting them. Would a sudden surplus of extra time — say, 30 minutes per appointment instead of 15 — lead to more patient-centered care? Could we spend that time addressing complex issues, such as mental health? Discuss costs with patients (which is what patients want)? Complete electronic health records in the office instead of charting at home? Perhaps with more time, clinicians would simply feel less rushed.

Fundamentally, when we think about patient experience, the question is, how can we remove barriers and create an environment for clinicians to better know and understand their patients? Clinicians and clinical leaders have interesting work ahead. Surveys like this can help us learn from one another so that we can improve health care as a profession. We need to have conversations about delivering value both to clinicians and patients.

Mari Ransco, MA

Director of Patient Experience and Value Engagement

Editor-in-Chief, Accelerate

University of Utah Health

NEJM CATALYST ANALYSIS

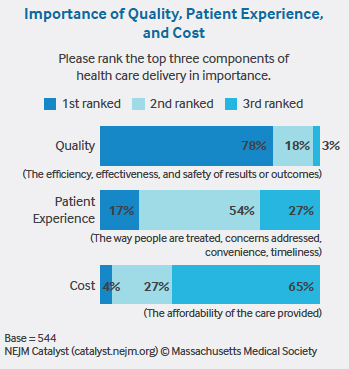

Patient experience is one of the most important components of health care delivery, according to a recent NEJM Catalyst Insights Council survey sponsored by University of Utah Health. “Word of mouth, insurance coverage, and online ratings bring people in the door, but patient experience keeps them coming back,” says David Carlson, MD, Medical Director at Great River Health System in West Burlington, Iowa.

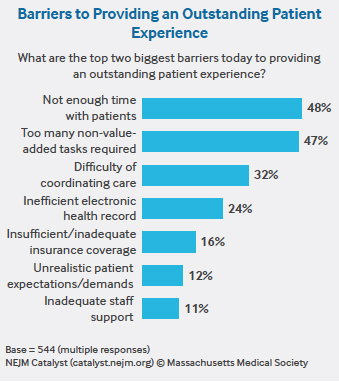

Ninety-one percent of respondents from the Insights Council, a qualified group of U.S. executives, clinical leaders, and clinicians directly involved in health care delivery, agree that providing an excellent patient experience is an essential part of achieving high-quality care. But there are many barriers to doing so. In the survey, Council members rank “not enough time with patients” as their number-one barrier to providing an outstanding customer experience (48%), with “too many non-value-added tasks required” as a close second (47%).

THE TIME CRUNCH

Like many physicians, Carlson is “under constant pressure to see more patients.” On top of his traditional patient visits, he’s now responsible for addressing population health for his patients. He calls it “the right work” but says it can be hard to find time to coordinate care.

Even at integrated health care delivery systems like Kaiser Permanente, which might seem to be insulated from the typical pressures around RVUs (relative value units), the time factor is felt. “There’s no protection from that anymore, as we’re all crunched to see more patients and to do more for them,” says Jake McKeegan, MD, Medical Office Chief at Colorado Permanente Group in Denver. Primary care physicians, who once were expected to see around 16 patients a day, are now in the 20-a-day range, according to McKeegan. As a result, physicians are pressured to work faster yet avoid harming the patient experience. “We are bending over backward to get people in who need to be seen and to make the patient portal easy to use, safe, and efficient,” he says.

Reginald Knight, MD, MHA, Vice President of Medical Affairs at Bassett Healthcare Network’s A.O. Fox Memorial Hospital in Oneonta, New York, says his clinic always runs behind. But he’s not willing to jeopardize the patient experience to speed things up. “I tell my patients, ‘We’re staying until we get your questions answered.’ We can’t always do that in a 15-minute slot, though.”

When it comes to having more time with fewer patients, a resounding 72% of clinicians surveyed agree that it would be worth it even if it means a reduction in revenue/income. “Most physicians started out with a very humanistic view of medicine, and we were idealistic about the care we wanted to provide,” says Richard Orlandi, MD, Professor of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, and Chief Medical Officer for Ambulatory Health at University of Utah Health. “Now, in this fee-for-service world, we’re on a treadmill, where speed defines our salary, and our salary is how we pay off debts from medical school and support our family. It creates this horrible tension between the care that we want to provide and the time that we’re allotted to provide it.”

Part of the time crunch is because of the survey’s second highest–ranked barrier — too many required, non-value-added tasks. Knight says that requirements such as checking boxes to meet metrics detract from being able to provide the best patient experience. “Patients see us as typing into a computer and not listening to what they have to say,” he says.

Orlandi agrees. “There’s a sacredness about the interaction between the provider and patient; if we project anything into that space that doesn’t add value, we are doing a disservice to the patient and provider.” Instead, Orlandi believes everything that doesn’t add value to the provider-patient interaction should be scrutinized. “Things that need to be done for documentation, billing, and quality measures need to be very aggressively looked at to make sure that the physician needs to do it versus someone else,” Orlandi says. “And, if it is the physician, then how can we maximize efficiency through EMR tweaks, process improvements, etc.”

MEASURING WHAT MATTERS

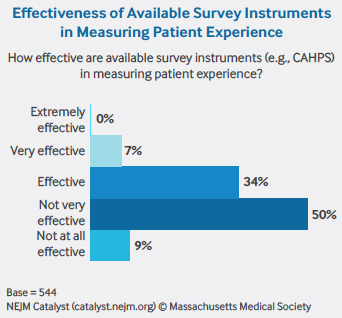

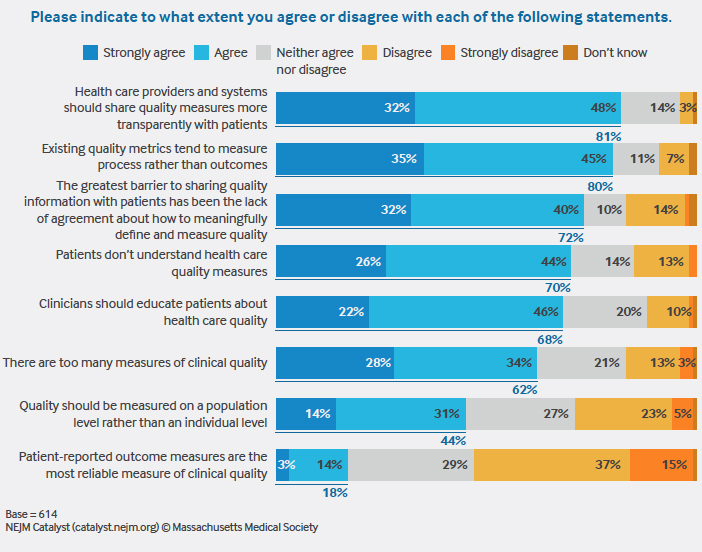

Ninety-seven percent of survey respondents say that listening to patients improves care. But capturing the patient voice and measuring it in a meaningful way is a difficult endeavor. Kaiser’s McKeegan is among the 59% of Council members who think survey instruments are ineffective at measuring patient experience. He considers the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems, or HCAHPS, to be “a foundational measure,” but says it and other survey tools like it lack personalization, granularity, and timeliness. “It’s hard to apply feedback from situations that happened nine months to a year ago,” he says.

What McKeegan would like to see instead is real-time scoring and comments that clearly illustrate whether the patient trusted the provider, felt the provider listened and understood the problem, and believed the provider was willing to work with the patient. The bottom line, he says, is that if patients don’t feel positive about these areas, they won’t come back – and they won’t recommend the provider to other people.

Like 89% of survey respondents, Knight believes patients conflate service (listening, access, convenience, and friendliness) with quality (outcomes and appropriateness). “If I didn’t give them antibiotics for a cold, I’ve provided quality care, but they might consider it a bad patient experience and that would be misrepresented in a feedback survey.” In addition, he says patient experience scores can be “reader beware,” just like “best doctor” listings, which often require the providers to pay a fee to be included. “Patients don’t understand that,” he says.

More than half of Insights Council members, 59%, agree that online reviews increase the likelihood that patients will choose a particular provider or health system. But only a third agree that online reviews of providers empower patients to make choices that align with their values and preferences. A higher percentage of executives (44%) than clinical leaders (30%) and clinicians (25%) agree about the power of online reviews to empower patient choice.

TRANSPARENCY: DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES

An even greater challenge is trusting the collective patient voice enough to share it transparently.

This winter, Colorado Permanente went live with public-facing reviews and star ratings. While McKeegan supports the overall idea of being transparent, he worries the public doesn’t have enough context around the data. “What if a physician has a more difficult panel and, therefore, spends more time with them? Will that negatively affect him? Also, how can we own the comments and be more reactive to them? I want to know how I can improve the experience.”

Carlson says he’d be more open to increased transparency if the feedback provided was actionable and forgiving. “I can’t be responsible for the overall experience of a patient in my panel I saw once five years ago in an acute care visit,” he says.

Although Orlandi understands the criticisms about public reviews, he believes there is value in it nonetheless. “I see how strongly people feel about sharing patient experience data and, yes, it’s somewhat imperfect,” he says. “But it’s better than relying on our own biased and imperfect perceptions of ourselves as providers. We can come away with a very positive feeling about our care and that’s important, but measuring the encounter from the patient viewpoint is equally if not more important.”

University of Utah Health has been aggressive in its transparency with consumers. In 2012, it became the first academic medical center in the country to electronically survey patients and post online reviews of physicians. The goal was to give patients enough data to make informed decisions and to recognize excellent work by providers.

The health system has made a concerted effort to focus on the emotion of an encounter versus just the rating, Orlandi explains. “It’s not just about a number, but rather the people represented in those numbers,” he says. “We focus on the comments to give data life. We all went into health care to take care of other human beings. Patient comments motivate us to want to do well for them.”

METHODOLOGY

• The NEJM Catalyst Buzz Survey was conducted by NEJM Catalyst, powered by the NEJM Catalyst Insights Council.

• The NEJM Catalyst Insights Council is a qualified group of U.S. executives, clinical leaders, and clinicians at organizations directly involved in health care delivery, who bring an expert perspective and set of experiences to the conversation about health care transformation. They are change agents who are both influential and knowledgeable.

• In October 2018, an online survey was sent to the NEJM Catalyst Insights Council.

• A total of 544 completed surveys are included in the analysis. The margin of error for a base of 544 is +/- 4.2% at the 95% confidence level.

NEJM CATALYST INSIGHTS COUNCIL

We’d like to acknowledge the NEJM Catalyst Insights Council. Insights Council members participate in monthly surveys with specific topics on health care delivery. It is through the Insights Council’s participation and commitment to the transformation of health care delivery that we are able to provide actionable data that can help move the industry forward. To join your peers in the conversation, visit https://join.catalyst.nejm.org/connect.

ABOUT UNIVERSITY OF UTAH HEALTH

University of Utah Health is the state’s only academic health care system, providing leading-edge and compassionate medicine for a referral area that encompasses 10% of the continental U.S. A hub for health sciences research and education in the region, U of U Health has a $291 million research enterprise. Staffed by more than 20,000 employees, the system includes 12 community clinics and four hospitals. For eight straight years, U of U Health has ranked among the top 10 U.S. academic medical centers in the Vizient Quality and Accountability Study, including reaching No. 1 in 2010 and 2016. For more information about our research in value in health care, visit uofuhealth.utah.edu/value/.

ABOUT NEJM CATALYST

NEJM Catalyst brings health care executives, clinical leaders, and clinicians together to share innovative ideas and practical applications for enhancing the value of health care delivery. From a network of top thought leaders, experts, and advisors, our digital publication, quarterly events, and qualified Insights Council provide real-life examples and actionable solutions to help organizations address urgent challenges affecting health care.

Nick McGregor is a Senior Communications Editor at University of Utah Health.