An independent NEJM Catalyst report sponsored by University of Utah Health

SPONSOR PERSPECTIVE

For many years, major stakeholders in the U.S. health care system have discussed how to ensure that patients consistently receive full value for the nation’s steadily growing investment in the health care delivery system. But exactly what value means has been unclear. Stakeholders, particularly systems and payers, have tried to act on component parts of value – cost, quality, and service – without collectively defining them or understanding how the relationship between them begets value. As a result, the term value has become a buzzword in health care – a popular slogan with unclear meaning.

If we as a country agree that we can, and must, provide higher quality health care and a better patient experience at a lower cost, then we need to better understand how other groups define and prioritize these three aspects of health care. To that end, University of Utah Health commissioned the Value in Health Care Survey to help clarify how three major stakeholder groups – patients, physicians, and employers who pay for medical benefits – perceive value. We chose these groups because they directly receive, provide, and/or pay for health care, and we believe their voices have not been heard clearly enough in the value conversation.

The survey found striking misalignments regarding how these groups define high-value care and who they hold responsible for making sure that happens. To further understand the perspective of practicing clinicians and health care leaders, University of Utah Health has partnered with NEJM Catalyst to administer a series of three surveys around cost, quality, and service. In the first survey we dug deeper into how these groups, particularly clinicians, view health care costs. We found that while clinicians feel a great sense of responsibility around keeping costs affordable for patients, they don’t feel they have the tools to know, the time to discuss, or the ability to impact how much things cost.

For the past 10 years, University of Utah Health has been on a value journey. While we’ve made bold moves and steady progress, we know there’s still a long way to go. As a country we must find ways to provide higher quality health care and better patient experience at lower cost. And as a first step, we need to better understand how all groups define and prioritize quality, cost, and service.

We’re grateful to NEJM Catalyst for partnering with us to explore this issue and thank all the members of the NEJM Catalyst Insights Council who participated in this survey. We hope the survey results will spark further conversations that will bring value into sharper focus and move us toward a collective vision for a value-focused health care delivery system.

NEJM CATALYST ANALYSIS

Mark Melrose, DO, is the Chief of Emergency Services at NYC Health + Hospitals’ North Central Bronx Hospital, a New York City safety-net hospital with 232 beds and more than 50,000 annual emergency room visits. Much of the care delivered by the organization is covered by government or commercial payers, and patients are usually unaware of the full cost. Melrose says it would be easy for him to assert that cost shouldn’t be a factor in the value equation and should remain hidden to patients and physicians alike. However, he considers that an irresponsible attitude, one that that winds up squandering the limited resources available in health care today.

“There needs to be universal transparency around costs on the buying and selling side of health care,” says Melrose. The question of cost of care and physician responsibility is the central theme of a recent NEJM Catalyst Buzz Survey, sponsored by University of Utah Health and conducted among the NEJM Catalyst Insights Council, a qualified group of U.S. executives, clinical leaders, and clinicians at organizations directly involved in health care delivery. The survey results show a disconnect: Physicians feel responsible for the cost of care to a patient, but not accountable for it.

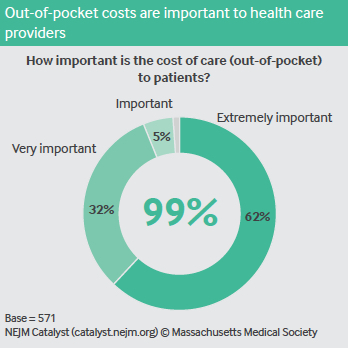

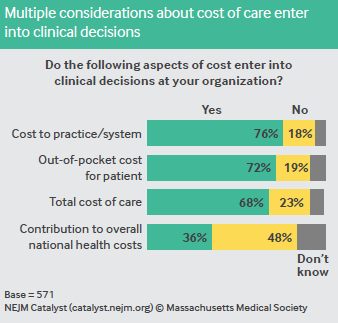

Respondents unanimously believe that outof-pocket costs are important to patients. The majority say that when making clinical decisions, the cost to the practice/system (indicated by 76% of respondents), out-of-pocket costs (72%), and total cost of care (68%) are considered at their organizations. More than 60% even say that physicians are responsible for educating patients about costs.

When it comes to accountability, however, nearly half of respondents believe physicians should not be held accountable for the cost of care. More clinicians (53%) than clinical leaders (44%) and executives (32%) feel this way.

“Physicians should definitely be aware of the charges generated by the treatments or prescriptions they recommend,” Melrose says. “Maybe they aren’t responsible for the actual cost, but they should be aware of the way they are contributing to the cost of care to a patient.”

In general, as patients deal with higher deductibles, co-pays, and premiums, along with less coverage in some cases, Melrose says financial awareness on the part of physicians becomes more important. “Depending on the time of year and the status of their deductible, patients could go to urgent care or the ER and be on the hook for literally thousands of dollars.” So, Melrose says, physicians must be in tune with the costs their patients incur.

Robert Glasgow, MD, Vice-Chair of Clinical and Quality Operations for University of Utah Health’s Department of Surgery and Chief Value Officer for the Department of Surgery in Salt Lake City, says he understands the hesitancy on the part of physicians to be accountable for the cost of care.

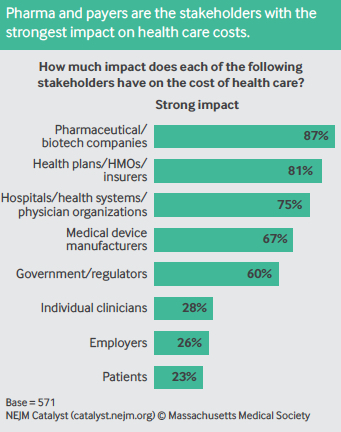

“Physicians don’t set pricing for insurance, and we can’t determine the price of a drug or a new technology, so it’s easy to feel powerless when it comes to impacting costs,” he says. “In an ideal state, all stakeholders would be accountable for costs.”

As it stands, though, survey respondents list pharmaceutical/biotech companies (87%), health plans/HMOs/insurers (81%), hospitals/ health systems/physician organizations (75%), and medical device manufacturers (67%) as stakeholders with the strongest impact on the cost of care. Individual clinicians (28%), employers (26%), and patients (23%) have the weakest impact.

“The people who are paying for health care, delivering health care, and receiving health care should have more power. They should be the ones to start the discussion and begin to influence the cost structure,” Glasgow says.

Before physicians can meaningfully have conversations around cost, though, Insights Council members say certain barriers need to be addressed, including:

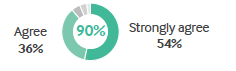

• The payer environment – 90% agree health care costs are too confusing with the current payer mix.

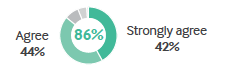

• Clinicians’ skill set – 86% agree physicians aren’t trained to discuss the cost of care.

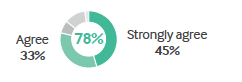

• The tools – 78% agree the tools necessary to estimate costs to the patient are not available, while 77% agree they are not available to estimate costs to the health system.

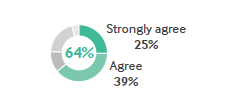

• Their time – 64% agree there isn’t enough time in clinic to discuss costs of treatments with patients.

Gillette Children’s Specialty Healthcare, a health system for children with complex medical needs in Minnesota, is immersed in tackling all of these barriers, according to Dennis Jolley, MPH, MEd, Vice President of Institutional Advancement and Chief Strategy Officer. Many procedures at the organization are scheduled well in advance, which allows time to consider their cost. “We do worry about cost to the patient and the total cost of care to our organization,” he says. “We try not to have [cost] circumstances influence the clinical decision-making by the clinician, but if there’s a less expensive option that meets the clinical need or a suitable MRI is available elsewhere, we work with the patient.”

Pediatric neurologists at Gillette Children’s have had to become familiar with some aspects of the payer mix among their spinal muscular atrophy patient panel. A game-changing drug for the aggressive disease that costs $140,000 per dose (more than $700,000 the first year and $400,000 for life) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration faster than the payers knew what to do with it, leaving certain patients uncovered. “The physicians don’t get into the detail of the individual payers, but they do understand there’s not consistency and there are pain points patients might be under,” Jolley says, adding “the families bear the bigger burden of the confusion from the payer market than the organization.”

Jolley believes care teams should work together to help patients understand costs. “You need clinicians seeing patients,” but burdening them with cost discussions would hurt productivity, he says. Social workers and other care team members can help.

At University of Utah Health, Glasgow says some patients, who travel long distances for medical attention, would be likely to better adhere to treatment or medication recommendations if there were an open discussion about the cost of care and their financial concerns. He warns, though, that physicians shouldn’t feel like they have to present patients with “an itemized bill” during these interactions. “The doctorpatient relationship should never be seen as a business transaction,” he says. “We need to train physicians to give patients enough cost data. That’s the starting block of high-value care.”

Chase Coffey, MD, MS, SFHM, FACP, Associate Chief Medical Officer at LAC+USC Medical Center, a 600-bed public teaching hospital serving Los Angeles County, says that accountability can start with physicians carefully reviewing the tests they order and the medication they prescribe. “Costs are definitely important to patients – even a $5 prescription. Therefore, we should make sure that only what’s appropriate and of high value are ordered and prescribed,” he says.

Coffey hopes a tool will come along that can put information about the patient’s insurance, drug formulary, and other details at their fingertips to maximize care. “It would need to be the equivalent of an ‘easy’ button – not a 300-page manual from an insurance company – and offer alerts about updates to costs and coverage,” he says.

University of Utah Health already has a tool that lets physicians know how much each patient costs down to the penny, but Glasgow doesn’t think that means physicians are ready to have those discussions. He hopes more education about how to talk to patients about costs will get the ball rolling. “Physicians should be stewards of the resource, and that means we can’t make ourselves immune to the cost of what we do,” Glasgow says.

METHODOLOGY

• The NEJM Catalyst Buzz Survey was conducted by NEJM Catalyst, powered by the NEJM Catalyst Insights Council.

• The NEJM Catalyst Insights Council is a qualified group of U.S. executives, clinical leaders, and clinicians at organizations directly involved in health care delivery, who bring an expert perspective and set of experiences to the conversation about health care transformation. They are change agents who are both influential and knowledgeable.

• In April 2018, an online survey was sent to the NEJM Catalyst Insights Council.

• A total of 571 completed surveys are included in the analysis. The margin of error for a base of 571 is +/- 4.1% at the 95% confidence level.

NEJM CATALYST INSIGHTS COUNCIL

We’d like to acknowledge the NEJM Catalyst Insights Council. Insights Council members participate in monthly surveys with specific topics on health care delivery. It is through the Insights Council’s participation and commitment to the transformation of health care delivery that we are able to provide actionable data that can help move the industry forward. To join your peers in the conversation, visit https://join.catalyst.nejm.org/connect.

ABOUT UNIVERSITY OF UTAH HEALTH

University of Utah Health is the state’s only academic health care system, providing leading-edge and compassionate medicine for a referral area that encompasses 10% of the continental U.S. A hub for health sciences research and education in the region, U of U Health has a $291 million research enterprise. Staffed by more than 20,000 employees, the system includes 12 community clinics and four hospitals. For eight straight years, U of U Health has ranked among the top 10 U.S. academic medical centers in the Vizient Quality and Accountability Study, including reaching No. 1 in 2010 and 2016. For more information about our research in value in health care, visit uofuhealth.utah.edu/value/.

About NEJM Catalyst

NEJM Catalyst brings health care executives, clinical leaders, and clinicians together to share innovative ideas and practical applications for enhancing the value of health care delivery. From a network of top thought leaders, experts, and advisors, our digital publication, quarterly events, and qualified Insights Council provide real-life examples and actionable solutions to help organizations address urgent challenges affecting health care.

Nick McGregor is a Senior Communications Editor at University of Utah Health.