An independent NEJM Catalyst report sponsored by University of Utah Health

SPONSOR PERSPECTIVE

Ask physicians what’s most important about the care they provide, and you can bet they’ll say high quality. In fact, a nationwide survey conducted by University of Utah Health found that 88% of physicians chose quality over patient experience or cost as the most important component of value in health care. That’s how we’ve been trained. That’s what distinguishes us. That’s why we continually strive to learn and improve.

But, as with many buzzwords in health care, what quality means is far from clear. And how we measure it is even more problematic. For the most part, we’ve left it up to the government to create thousands of metrics — and largely settled on measuring processes. We check boxes to indicate we’ve administered antibiotics, taken blood pressure, offered smoking cessation tips... the list goes on. What’s eluded us, however, is how we measure the effect of all those efforts to improve a patient’s life — in the short term and, even more impossibly, over the long haul.

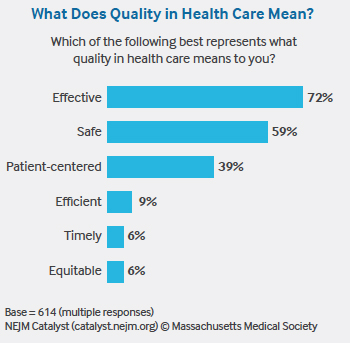

Furthermore, there’s a disconnect between how we define quality and how patients think about it. Most clinicians define quality care as being “effective” and “safe.” Most patients, however, assume their care will be safe and effective — just like they assume their airline flight will safely transport them to their destination. Patients also don’t understand health care quality measures, according to the majority of NEJM Catalyst Insights Council survey respondents. If that’s the case, we have to admit that we haven’t made it easy for them to do so. Respondents agree we have too many measures of clinical quality, they’re not meaningful, and we haven’t shared them transparently with patients. Is it any wonder, then, that patients use substitutes such as friendly staff, convenience, access, and trust to determine quality?

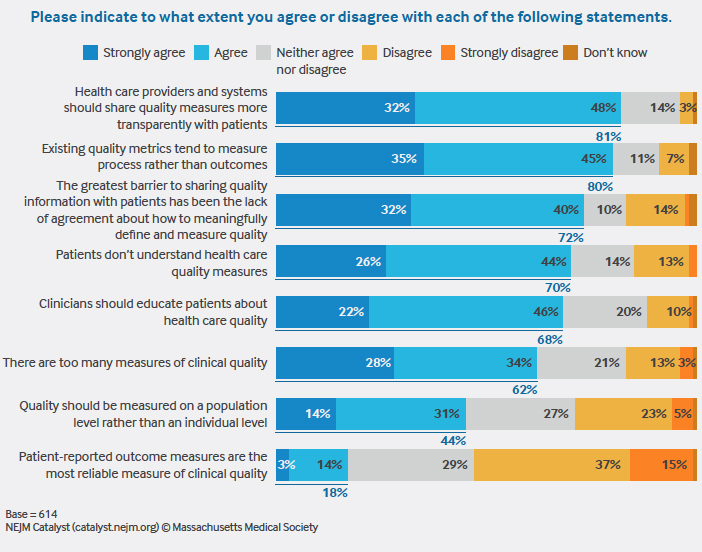

We can lament the confusion, or we can start to bring patients into the conversation. Six years ago, University of Utah Health became the first academic medical center to post online patient reviews of physicians — complete with a five-star rating system. It wasn’t easy, but we were committed to listening to the patient, and now it’s part of our culture. Today, we are figuring out ways to incorporate the patient voice into our quality metrics by focusing on patient-reported outcome measures. This will also be challenging, especially considering only 18% of survey respondents agreed that patient-reported outcome measures are the most reliable measure of clinical quality.

The solution is complicated, but one thing is clear: Clinicians and clinical leaders need to engage. Surveys like this one can help us become more self-aware so that we can begin to have the difficult and productive conversations we need to have.

Tom Miller, MD

Chief Medical Officer

University of Utah Health

NEJM CATALYST ANALYSIS

Quality of care has become a primary health care measurement to rate performance, determine reimbursements/incentives, and attract new patients. Yet, according to a recent NEJM Catalyst Insights Council survey on quality of care, today’s quality measurements present significant problems that can hinder the sharing of data, especially with patients.

“There are too many metrics, we aren’t measuring the right things, and patients don’t seem to care about quality in the same way we do,” says Tom Miller, MD, Chief Medical Officer at University of Utah Health.

The survey, sponsored by University of Utah Health and conducted among a qualified group of U.S. executives, clinical leaders, and clinicians at organizations directly involved in health care, finds that although providers overwhelmingly favor sharing data with patients (80% strongly agree or agree that quality measures should be more transparent to patients), they are wary of the current limitations of quality data and patients’ understanding of quality’s definition and value.

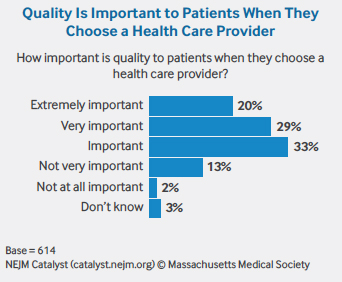

Their concerns are deep-seated: 72% of respondents agree that a lack of consensus on how to meaningfully define and measure quality has been the greatest barrier to sharing information, and 62% of respondents agree that too many quality metrics exist. And while most respondents (82%) believe quality is important to patients when they choose their health care provider, 70% agree that patients don’t understand quality measures.

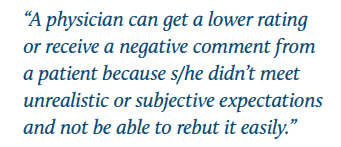

The result: Providers worry that poor quality metrics not well understood by patients could impact them negatively in terms of reimbursement and reputation.

“There are real problems with today’s metrics that could reflect poorly on clinicians and make them feel vulnerable,” says Susan Nedorost, MD, Professor of Dermatology and Quantitative and Population Health Sciences at Case Western Reserve University, and Director of Graduate Medical Education at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center.

As an example, Nedorost says measurements that focus on how quickly a patient is relieved of pain create an incentive to prescribe treatments that have an immediate effect on patients, even if those treatments may put the patient at risk for other health problems later.

Nedorost experiences this issue among her own patient population. Patients diagnosed with dermatitis are often prescribed steroids multiple times a year to relieve the symptom of itching. Nedorost performs a patch test to identify contact allergens, then counsels patients on alternative, allergen-free personal care products that might cure their dermatitis. By following best practices and taking a more prolonged approach, she says she risks getting dinged with financial penalties, lack of reimbursement, or poor ratings, even though she is providing what actually is high-quality care.

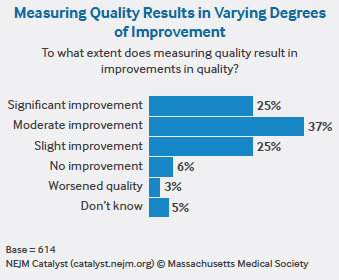

To Miller, the problem comes down to measurements that are more focused on process than outcomes — and 80% of respondents also agree this is the case. “Measuring processes is simple,” he says. “Measuring how effective care is will be a much more meaningful, but difficult, endeavor.”

Take screening for depression as an example. “You can report that every patient in your clinic was screened for depression, which is what providers are currently evaluated on,” Miller says. “But if you found depression, what did you do about it? Did your treatment work? Or did the patient leave your office and eventually harm themselves? That’s what we haven’t figured out — how we measure if our care was effective — and that’s what really matters.”

For quality to be considered “effective” — the top definition chosen by 72% of respondents — Miller believes that a more longitudinal view of each patient is required. Today, it is far too episodic. “Patients travel in and out of systems and insurance providers,” Miller says. “With quality, you want to be able to see how your patient did in the short term and over the long haul.” However, Miller isn’t sure who could compile that history. Options include national registries or insurance companies, but neither, in his opinion, are up to the challenge yet.

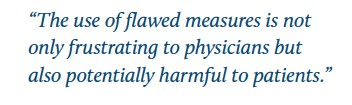

As the health care industry undertakes this effort to aggregate and analyze more data, it would be helpful to pare down metrics and better validate them, Miller says. He points to a recent study by the American College of Physicians evaluating a subset of the performance measures included in the Medicare Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS)/Quality Payment Program (QPP). The committee found that 37% of the performance measures rated as valid, 35% as not valid, and 28% of uncertain validity.

“Our analysis identified troubling inconsistencies among leading U.S. organizations in judgments of the validity of measures of physician quality,” write co-authors of The New England Journal of Medicine article “Time Out — Charting a Path for Improving Performance Measurement.” “The use of flawed measures is not only frustrating to physicians, but also potentially harmful to patients.” Although more than two-thirds of respondents say clinicians should educate patients about health care quality, it is clear that the flaws in quality measures make this task more difficult.

So how does the industry get to more comprehensive, standard, meaningful, and accurate quality metrics? Seek out the patient voice and increase transparency of those findings, according to Miller. “The industry has been struggling at this,” he says. “Maybe we should shift our thinking and have patients define what is meant by good quality.”

Marc S. Rovner, MD, MMM, CPE, Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine for the Department of Pulmonary Critical Care Medicine at Indiana University Methodist Hospital in Indianapolis and Medical Director for COPD Population Health, says it is difficult to espouse quality when, “for many patients, quality is not the most important discriminator when choosing a doctor.”

Kate Cronan, MD, Attending Physician for Emergency Medicine, Director of Health Content Integration, and Medical Editor for the Center for Health Delivery Innovation at Nemours Children’s Health System, says bringing quality to the forefront starts with making metrics more accessible to patients. “If patients understood what quality means in their language, they would think it is highly important,” she says.

Many patients are putting their trust in online review sites, where consumers voice their opinions about their care. “Patients are finding information online already, and physicians want to be the one to give them context,” Cronan says.

“Patients are looking at availability, affability, affordability, and ability… in that order,” Rovner says. But many patients choose their doctor by word of mouth, are assigned a physician when they visit the hospital, or follow the advice of their primary care provider. “The greatest threat to the accurate reporting of quality data is not the government, it’s social media sites like Angie’s List,” he says. “Transparency is an antidote to skewed ratings and can provide a competitive advantage, as well as be more objective.”

“Patients are using satisfaction and experience scores as a proxy for quality data metrics — but they aren’t the same,” Miller says.

To stem this tide, Miller recommends patientreported outcomes, feedback solicited directly from the patient that determines how he or she feels health-wise and what he or she can physically do. Still in their infancy, more than half of respondents rejected patient-reported outcomes as the most reliable measure of clinical quality. But, in Miller’s view, they could help to introduce the patient voice into quality metrics.

Providers worry that outcomes may not reflect the complexity of particular cases. The pushback Miller has seen revolves around three questions: Should patients be the arbiter of quality? Are there meaningful, accurate, and standardized ways to measure patient-reported outcomes? How can the industry overcome the lack of experience in effectively utilizing patientreported outcome measurements as a means to improve care?

“Herein lies the tension,” Miller says. “As our outcomes improve and perfection is expected, will we be held accountable for the entirety of the experience? I believe that answer is ‘yes.’ Perhaps our best defense arises in our ability to have meaningful conversations with patients along the continuum of care, a thing that doesn’t exist in the 15-minute visit.”

As quality becomes deeply entrenched as a reflection of performance, the health care industry is going to have to improve quality metrics and broaden its reach to include the patient voice.

METHODOLOGY

• The NEJM Catalyst Buzz Survey was conducted by NEJM Catalyst, powered by the NEJM Catalyst Insights Council.

• The NEJM Catalyst Insights Council is a qualified group of U.S. executives, clinical leaders, and clinicians at organizations directly involved in health care delivery, who bring an expert perspective and set of experiences to the conversation about health care transformation. They are change agents who are both influential and knowledgeable.

• In July 2018, an online survey was sent to the NEJM Catalyst Insights Council.

• A total of 614 completed surveys are included in the analysis. The margin of error for a base of 614 is +/- 4.0% at the 95% confidence level.

NEJM CATALYST INSIGHTS COUNCIL

We’d like to acknowledge the NEJM Catalyst Insights Council. Insights Council members participate in monthly surveys with specific topics on health care delivery. It is through the Insights Council’s participation and commitment to the transformation of health care delivery that we are able to provide actionable data that can help move the industry forward. To join your peers in the conversation, visit https://join.catalyst.nejm.org/connect.

ABOUT UNIVERSITY OF UTAH HEALTH

University of Utah Health is the state’s only academic health care system, providing leading-edge and compassionate medicine for a referral area that encompasses 10% of the continental U.S. A hub for health sciences research and education in the region, U of U Health has a $291 million research enterprise. Staffed by more than 20,000 employees, the system includes 12 community clinics and four hospitals. For eight straight years, U of U Health has ranked among the top 10 U.S. academic medical centers in the Vizient Quality and Accountability Study, including reaching No. 1 in 2010 and 2016. For more information about our research in value in health care, visit uofuhealth.utah.edu/value/.

ABOUT NEJM CATALYST

NEJM Catalyst brings health care executives, clinical leaders, and clinicians together to share innovative ideas and practical applications for enhancing the value of health care delivery. From a network of top thought leaders, experts, and advisors, our digital publication, quarterly events, and qualified Insights Council provide real-life examples and actionable solutions to help organizations address urgent challenges affecting health care.

Nick McGregor is a Senior Communications Editor at University of Utah Health.