Voices of U of U Health

Science Careers Are Made Here

To establish a career in biomedical research, there is no better place than University of Utah Health. It’s full of fresh ideas, imaginative and collaborative colleagues, curious students, and extraordinary stimulation. For recharging, it’s located within easy access to a spectacular outdoor world. There is a unique combination of people and resources here with no barrier between wilderness and work.

At institutes of higher learning, few things matter to me more than creative energy. When you think about biomedical science, creativity might not be the first thing that comes to mind. Our first impressions are more along the lines of: “This is serious” or “We need a quick solution, it demands expertise, therefore we need to be competent and professional.” Sometimes I think we forget—or we undervalue—adding creative spirit or creative energy to the mix. So why is that so important in biomedical science? It’s because this is how humans have always faced the world. You face a problem or a challenge, and the really interesting ones are those that cause you to pause and ask, “How do I do something that was never done before?”

Aligned for Creativity

There is a high level of creative energy here—not just at the university but in the culture of this community and state. To be successful in science, we can't just fall back on what we've done before. We can't fall back on what we think we're supposed to do. We must have a little bit of courage to try something new. In its geography and its culture, Utah has this energy. The stars are aligned to spend time in creative space, whether it's the inspiration of the wilderness around us or colleagues who are also pushing forward, bringing you to the edge of a cliff, and daring you to jump over. Utah just has that. That's been a gift for many generations of scientists here to lead the way by being daring and creative.

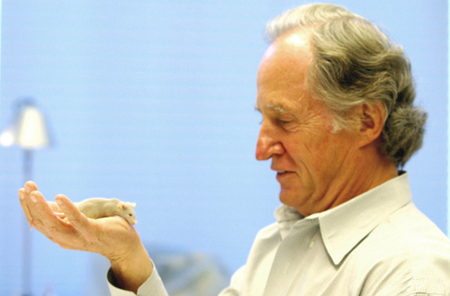

When a scientist has a spark of imagination that might lead to a discovery or provide a reason to delve into something that no one has explored before, that brings joy. It’s why science is fun. I had a conversation with Mario Capecchi, PhD, recently that reminded me of this outlook. He is also a practitioner of having fun and centering scientific work around having fun. That is how we all grew up—or, even as young scientists, the reason we got into the game or the profession is because it was fun. You are curious and want to use your creativity to understand the world around you. Most kids do this naturally. Children’s science museums have this down pat; there are all sorts of interactive exhibits that naturally feed that curiosity, enhance it, and grow it.

Then, somehow, as we mature and continue in our careers, life’s necessities and the business side of things can infiltrate, and we risk losing our balance. We should all visit science museums and exercise our creative impulses.

Mario Capecchi As Mentor

Capecchi is a big reason I opened my lab at the U. When I arrived 10 years ago, I was awarded the first Mario Capecchi Endowed Chair of Genetics. The chair was a direct outcome of his Nobel Prize and given by The George S. and Dolores Doré Eccles Foundation. Spence Eccles wanted to endow the chair to celebrate Capecchi winning the U’s first Nobel Prize. What a great opportunity that was for me to be connected to and mentored by someone who personifies scientific courage.

For scientists early in their careers who might wonder about the opportunities at U of U Health, I would tell them first that this university is really good at offering a hand. That may be my best piece of advice. Take advantage of what is available here. Don’t go alone. Reach out, use your colleagues, and make use of the abundant resources around you. I think the University of Utah is finely tuned to be collaborative, to be helpful, and to build teams. It's a balancing act, of course, between starting something that's your independent thing but also leaning on the resources and tools that are here for you. The Capecchi chair has now changed hands several times, with new faculty opening labs here after me. Wouldn’t it be incredible if every new faculty could build a lab with these kind of resources in place? That’s something to dream about into the future, and at Utah, we might be on the way to making this a reality.

I feel as though I have a responsibility to really embrace some of the significant investments in my science, especially after my selection as a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) investigator. It’s exciting to be recognized and an amazing opportunity and responsibility knowing that I’m joining a community of interesting, innovative scientists who have been given the freedom to explore uncharted scientific territory. I want the investment from HHMI and the one from the MacArthur Foundation to pay off. I've been conducting research on evolutionary genetics for a while, but now with even more investment, I’m hoping to move in some surprising directions. I’m eager to do something that feels unfamiliar.

Uncharted Waters

It's a balancing act of course, to do that. The trick is to point the ship not into a safe space but in a new direction that feels unfamiliar. If I’m doing it right, I’ll feel like a novice and not know what I'm doing! Then, after some stretch of time, something new and interesting, from an unforeseen direction, will present itself. I can't put my thumb on that today, but maybe that’s why this kind of recognition exists, or where these fellowships come from. At my U of U Health lab, we’ve been able to do this a couple of times now—to take a few chances or put ourselves in an uncomfortable space productively. I'm hoping to do that again. This is a science agenda fueled by creative energy.