Voices of U of U Health

Beyond the Drug Store

In spite of the stereotypes, pharmacists do more than count pills at the neighborhood Walgreens. While many do work behind a counter on Main Street, other pharmacists perform countless surprising roles in health care, industry, and government. They are the primary sources of drug-related information for patients, policymakers, and health care providers.

Karen Gunning, a pharmacist, and Karly Pippitt, a physician, look back over the history of the pharmacy profession and consider how critical it is today.

Dr. Gunning: At Oregon State in the early 1990s, my pharmacy classmates and I were told we would one day be replaced by computers. That is, unless we learned how to talk to people. That was the very beginning of my career working with provider teams to impact care as a go-to medication expert.

Now, as a clinical professor at the College of Pharmacy (COP), I train students in the specialty of pharmacotherapy. I also work with the School of Medicine’s Family Medicine Residency Program. That’s how Karly and I got to know each other.

Dr. Pippitt: I’m an associate professor of Family & Preventive Medicine. I also practice family medicine. Karen and I have had a front row seat as we’ve witnessed dramatic changes in the field of pharmacy during the last 20 years. The role of pharmacists has expanded, especially in how they work with physicians.

Dr. Gunning: Before the 1950s, prescription drugs were not a thing. A person would simply go to a pharmacy, where the pharmacist would concoct a compound to treat their symptoms.The era of prescription drugs only began as drug regulation became more prevalent. Pharmacists became medication dispensers. In the 1960s and early ‘70s, pharmacists weren’t allowed to talk to patients about their medications. For some prescriptions a pharmacist was not even allowed to put the name of the medication on the prescription bottle.

Dr. Pippitt: That is almost hard to believe considering how much patients want to know these days. The more involved a patient is in their health care, including useful information about medications, dosage, side effects, and so on, the better their health outcomes.

Dr. Gunning: The movement toward clinical pharmacy began in the mid-1970s. Pharmacists became more engaged in decision-making about what medications were most appropriate. This began in hospital pharmacies. Actually, the department of pharmacy practice here at University of Utah’s COP was one of the real innovators of the modern clinical pharmacy. But soon, patients began to view their retail and community pharmacies as more than just places to fill orders from a physician. They began looking for expertise about their prescriptions.

Dr. Pippitt: In medical school, I had minimal training in over-the-counter drugs. But during residency, pharmacists helped educate me—and my patients—on giving advice about these medicines, which have gotten more complex over the past 15 to 20 years.

Throughout my training, there was always a pharmacist in outpatient settings. In the inpatient settings, some teams included a pharmacist who saw patients with us. Sometimes, the pharmacist was only available in the hospital. I distinctly remember being in the ICU and pulling out my drug pharmacopeia to look up drug dosing. The pharmacist in the ICU scooted up to me and said, “What are you looking up? Just ask me. I'm right here.” With the advent of more and more medications, having a pharmacotherapy specialist becomes vital.

Now, I don’t want to practice without a pharmacist.

Dr. Gunning: The broader the knowledge needed for the medical profession, the more people want to work in teams. Most family physicians realize there is no way they can learn, for example, all 30 new drugs for diabetes.

We started a four-year Doctor of Pharmacy program in the early 2000s, transitioning from a bachelor’s in pharmacy and a post-baccalaureate two-year PharmD. Our students do six-week clinical rotations in a variety of settings. They may spend six weeks with family medicine at a health center, then maybe six weeks in ICU, six weeks in Panguitch at a community pharmacy, and six weeks in Blanding at the Utah Navajo Health System Pharmacy and Clinic. The pharmacy students get a wide variety of experience.

But we're also teaching them more about talking to patients—so they don’t get replaced by computers, right?

Motivational interviewing. Understanding social determinants of care. How to be culturally responsive and inclusive. It is a real shift in thinking for our students as they go beyond just taking a prescription and ensuring it's filled correctly. Instead, they develop a plan for a patient, working with other providers on the patient’s health care team.

Dr. Pippitt: As a physician, I admit that some MDs have been resistant to having non-MDs right there as part of the care team. But when pharmacists are actually embedded in the health system, some of that resistance fades. Knowing you have a team helping you deliver the best care possible lifts some of the burden physicians feel. This certainly helps with physician retention, relieving burnout, and maintaining wellness, which are all huge issues right now.

Dr. Gunning: Similarly, it wasn't until 2010, soon after the H1N1 flu pandemic, that all 50 states authorized pharmacists to administer vaccinations. Think about administering COVID vaccines now. If we could not utilize the pharmacy workforce, including certified pharmacy technicians, we would be in a world of hurt.

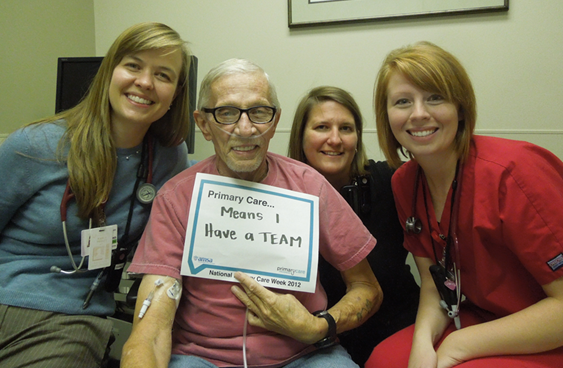

Dr. Pippitt: We could talk all day about the necessity of pharmacists for better health care. At a primary care clinic, having pharmacists as a patient resource is critical. Patients often consider pharmacists more approachable than physicians. With diabetes in particular, a lot of people don't feel comfortable talking to their physicians because they haven't kept up the arduous daily routine the doctor has suggested. Clinical pharmacists can serve as that intermediary with an unspoken message of, “We're not here to judge you. We're here to help you.”

Dr. Gunning: I’ve always told patients to take a deep dive into their medications, to always question whether they should be on a drug or not. I hope patients anticipate that a pharmacist will be present in a primary care clinic, and that they are available to them if they have questions.

When I talk to high school students or pre-pharmacy students, I find it’s hard for them to know what a pharmacist does—what I do. I’m not in a white coat in a retail chain behind glass. A big goal for the College of Pharmacy is to spread the word and make it clear that pharmacists play a vital role in every part of health care.

When I tell young people about pharmacy’s expanded role, it can really open their eyes about our work. I see a lot of interest in opportunities like informatics, pharmacy computer systems, and decision-making tools for drug therapy.

I often tell patients I’m a pharmacist without a pharmacy. The impact of pharmacists goes beyond a physical building. With more pharmacists on care teams in the future, we can ensure that patients are getting the safest, most appropriate drug therapy to help them live happy and healthy lives.

If you don’t have a pharmacist on your health care team, ask for one!