Voices of U of U Health

Mental Health Care in a Pandemic

We’re all more than a little shaken. And tired. And stressed.

Since March, the University of Utah Huntsman Mental Health Institute (HMHI) formally University Neuropsychiatric Institute (UNI), has observed a significant increase in calls to our CrisisLine and WarmLine. Call volume increased almost 25 perent in May. Mental health providers are noting increases in the self-reporting of stress, anxiety, depression, fear, and suicidal thoughts, even among people who do not have a prior psychiatric history. Individuals are talking about their worry of the unknown because of the pandemic, relationship strain, physical isolation as a family, transitioning to working from home, economic uncertainty, and social justice, all while expressing fatigue and, for some, a sense of hopelessness.

Suicide rates tend to slightly increase in times of economic and social crisis. Studies have shown that rates increase around 4 percent within the two-year time period following an economic crisis. In the U.S., older males who have experienced a higher percentage of income loss are the most at risk for suicide. This can be helpful information when looking at specific populations to support.

A useful model to help us understand the strain we are enduring is “allostatic load.” This is “wear and tear on the body,” which can accumulate as individuals experience prolonged strain. It can have physiologic changes in all systems of your body and cause mental health disruptions in addition to fatigue and apathy, symptoms we are starting to see more in our everyday life.

There is another term, resilience, which is often discussed when we talk about counteracting the effects of stress. This is the level that a person can “bounce back” from a negative outcome or stressful situation. There are things you can do to actively build this mental toughness.

Below are some tips that you can do in your everyday life to reduce your allostatic load and improve your resilience. While some are familiar, we’ve created a new way of looking at recommendations.

1: Movement

The benefits of exercise are well-known, but conceptualizing it as movement may help you initiate this behavior change if you’re not currently moving much. Cleaning out a cluttered space, playing a lawn game, dancing with your kids, or pairing a phone conversation with a walk are all small steps that can add up to a big difference in your activity level.

2: Nutrition

It is important to remember to eat a variety of foods daily, noting what gives you energy and what leaves you tired. Eating mindfully (paying attention to when you are hungry and full, avoiding snacking while distracted, and recognizing thirst) is a way to improve your nutrition. Nourishment will help on a cellular level as well as a physical stamina level.

3: Social Contact

We are social beings and respond on a physiologic level to touch, talk, and laughter. During times of physical distancing, it is important to stay connected to your friends and family. While virtual contact is increasingly accessible, being able to connect with another person can help reduce your strain. Many people have a “COVID circle” that commits to the same level of physical distancing. Meeting people in open air while masking & moving or sitting six feet apart in the back yard can help you feel less alone. Additionally, service to others has been shown to have psychologic benefits on mood: becoming active in social justice groups, sewing masks, checking on a neighbor, and watching out for the needs that are expressed by others in your everyday life are small ways that you can start to connect and benefit yourself as well as others.

4: Limiting Media

Ensuring information sources are reliable, credible, and not sensationalized can have a big impact. Turning off your screen and picking up a book or listening to a book electronically while driving to work can be helpful stress reducers. Libraries are now open for pick-up and are a great free resource for your family.

5: Limiting Alcohol and Avoiding Mood-altering Drugs

A drink during stressful situations is a welcome reprieve to some that can lead to increased consumption and interfere with the behavior changes being described, especially as we remember alcohol is a depressant. Creating a different ritual for unwinding after work (spending 20 minutes gardening, watching a funny show, putting lotion on your dry hands) can set your evening up for better sleep and productivity.

6: Sleeping

Sleep is such an important time for our bodies and minds. It is often overlooked in our fast-paced culture as a basic strategy to improve mood and energy. Additionally, sleep lowers your risk of heart disease, stroke, cancer, and obesity. Sticking to a scheduled bedtime and waking up at a consistent time are shown to be helpful in regulating sleep cycles. There are many helpful articles on sleep hygiene with specific tips on how to improve your sleep.

7: Perspective

While guidelines are constantly changing, it is important to remember that our ability to adapt is remarkable. Looking at the big picture of this period in time, reminding yourself this is temporary, and finding any positives are great techniques to reduce your stress. Taking brief mental breaks during the day and having a gratitude practice are simple ways to reduce your mental load. Comparing your life with other cultures and countries can offer a perspective shift as you recognize that there are a lot of hardships that people can endure.

8: Help

Recognizing when emotional strain becomes overwhelming and seeking professional support from a clinician can reduce the duration and intensity of an episode of depression. Additionally, many anxiety disorders can be resolved through a combination of behavioral techniques and medication.

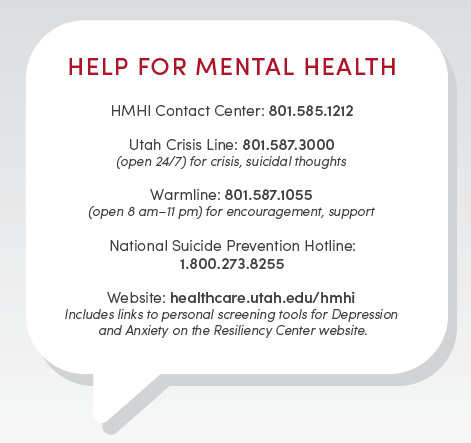

It is more important than ever to actively practice wellness activities and seek support from professionals if your level of fatigue, worry, or mood are impacting your ability to get through your day. We are here for you!