Voices of U of U Health

Tip of the Sword

“I have received so many inspiring messages from our frontline care teams who are battling the COVID-19 pandemic, and I wanted to share them. I asked our communications team to follow up with a few of those heroic providers and ask them to share their stories." — Michael Good, MD

On the COVID-19 Frontline, University of Utah Health Providers Discover a Deeper Connection to Their Vocation

When the first patients suspected of having COVID-19 filtered through the emergency department into the University Hospital in early March 2020, only one of the hospital’s eight hospitalist teams was initially dedicated to their care in order to limit provider contact with the virus.

Team Eight was chosen. That put Emily Signor, MD, as a sole physician in charge of their care during the day shift. Signor, barely through her first six months as a hospitalist, was starting to find her stride as a physician on the team. Colleagues besieged her with supportive texts and calls. “It was like having ten parents,” she says.

The first dozen patients tested negative. Signor felt her work akin to a stressful dress-rehearsal of new and evolving PPE protocols and policies. Then a test result on a male patient stopped her in her tracks. “Detected,” it read. When she told the patient he was positive, he seemed almost relieved at the news.

His reaction made her realize that despite the gravity of the diagnosis, he found some comfort in at least knowing they could now talk about treatment, rather than being in the agonizing limbo of waiting for the result. From then on, she says, she tried to ensure that the insight that first patient afforded her into the importance of dispelling uncertainty, was one she could apply to all her subsequent COVID-19-suspected patients. In essence, she paraphrases, “Now that we know, we can move forward with a little more resolution.”

For Signor, nurse practitioner Gene Scerbo, and critical care registered nurse Maria Theresa “Tess” Javellana, COVID-19 has brought them a deeper commitment to a vocation already intimately woven into their lives. It’s a commitment made all the more apparent as they have found themselves part of a health care apparatus stripped to its key clinical staff. “You feel like you are part of the tip of the sword,” Scerbo says.

All three providers have roots in service. Scerbo went to a work-learning-service college in North Carolina. His professors told him, “If you have an ability to help others, then you have an obligation to do that,” he recalls.

Yet that passion for serving others has been confronted by a virus that denies them something they love about their profession: their connection with patients.

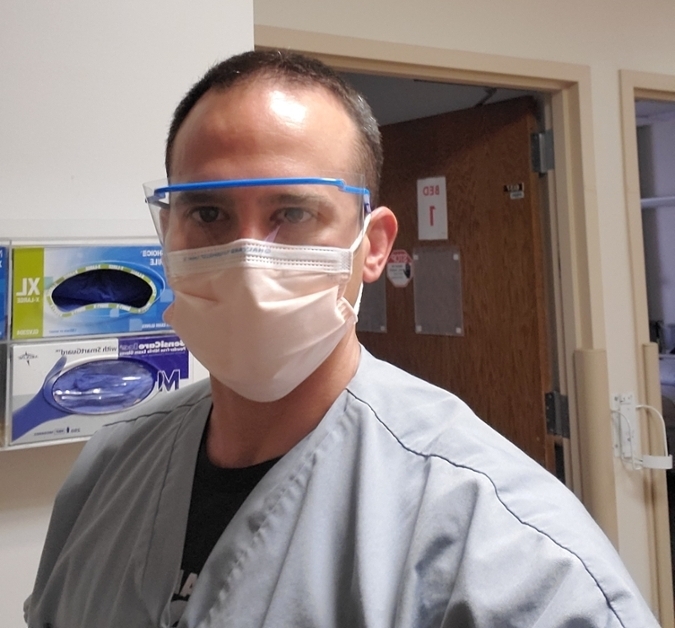

Patients face a painful, frightening isolation. “We come into the room, gowned, gloved and masked,” says Signor. “We are all attempting to be in the room as little as possible to minimize exposure. They can’t have visitors. You can’t imagine the anxiety patients have.”

That’s deeply frustrating for providers used to offering sympathy, understanding, and the comfort of their presence. “There’s a compassion wall,” says Scerbo, who is also part of a hospitalist team. “You don’t feel like your level of compassion can get through it to your patient. You feel guilty you can’t provide a hand on their hand; ease the burden of their disease.”

In the age of physical distancing, this extends to carers themselves at work. Rather than consult with the patient in their room, Signor and Scerbo communicate from separate rooms alone by phone. The first time Signor meets a patient, she drops their phone in their lap. “Please answer when it rings,” she tells them. She and Scerbo spend a lot of time on the phone talking to patients and patients’ families every day.

Then, still alone, they do their documentation. “One of the things I love about medicine is it’s a team sport,” says Signor. “It’s hard to get fulfilment from that perspective when everyone has to stay in separate rooms.”

That experience has taught her something valuable. “It’s important for me to know each patient as a human being, with thoughts and emotions. It’s something I want to continue to emphasize in my career.”

Isolated from colleagues, Scerbo finds support. “Even though you are not able to pat them on the back, you can support each other with words. If the teams are strong, you know you’re not alone, there’s backup for you in any situation.”

Scerbo says his work “feels significantly more essential than it did two months ago. I deliver essential care efficiently to infected patients so they can be moved out of the hospital and into isolation to recover.”

That vital role means he doesn’t mind picking up additional night shifts. “Maybe at the hospital I’m able to see five more people,” he says. “And because of my efforts, maybe a nurse doesn’t have to be exposed to five more people down the road. You feel far more part of a team. Everyone is working to the same goals.”

Along with their patients, front-line providers worry about loved ones, relatives, and friends at home and abroad. Javellana works in acute internal medicine A50—known informally as the “COVID unit” in the hospital—caring for patients who may be infected. She migrated to Utah in 2008 and has friends from the nursing college she attended in the Philippines who, like her, went abroad in search of work. Online, her international circle of nursing colleagues share their fears. “Their lives are at stake; they still go to work,” she says in tears. “They don’t feel protected. It’s really sad. Some have already died. I feel so blessed. I always share to them there’s also hope for us.”

Treating COVID-19 patients brings the risks inherent in providing care for others into sharper focus. “It’s important that people know that nobody who is doing this right now begrudges the general public,” Scerbo says. “This is what we do, what we want to do, otherwise we wouldn’t be in this profession.”

Along with the risks also emerges a deeper sense of commitment to their profession. Javellana has realized that her work “is what I’ve been preparing for all my life.” Like Scerbo and Signor, Javellana finds fulfilment every day in her profession. “You make a difference in someone else’s life. You give them inspiration and hope that it’s not as bad as they think.”

They all view their vocations with the same crystal clarity as Javellana, when she says, “This is what I chose, and I’m ready for whatever’s going to happen. I love what I do, and every single day I go to work I have no regrets. I am a nurse.”

Want to Help?

Our community is our greatest asset, and whatever help you can give, we are truly grateful for. Support Our Response