Jennifer Hampton Hill, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in both the Round and Murtaugh Labs in the departments of pathology and human genetics at the University of Utah, was named the grand prize winner of the NOSTER & Science Microbiome Prize. The prize rewards innovative research by young investigators working on how an understanding of microbiota—the bacteria, viruses, and fungi that live in our bodies—contributes to health and disease, or guides therapeutic interventions. For her novel and impactful science, Hill earned $25,000 and her winning essay published in the journal, Science.

“There is amazing and fascinating work being done all across the microbiome field, and to be selected from it is a huge honor,” says Hill. “My work has also been supported by remarkable mentors and colleagues, and it certainly wouldn’t be possible without them. I’m incredibly grateful.”

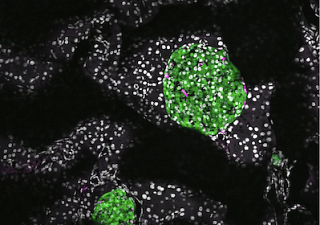

In her essay, “From Bugs to b-cells” Hill describes identifying an extraordinary connection between Type 1 Diabetes and our resident microbiome. Animals that have no microbiome have fewer of the b-cells that produce the insulin that the body needs, and are prone to a diabetes-like condition. Further, Hill found that a specific factor produced by microbiota helps the insulin-producing cells to grow.

The discovery not only opens doors to new therapeutic approaches to Type 1 Diabetes, it also adds to a growing appreciation of our relationship with the environment in which we live. The “hygiene hypothesis” says that over-sanitized homes and workplaces may be altering the microbiome within us. Hill’s work shows how that change could tip the balance, contributing to the onset of diseases like diabetes.

“It has become clear that our resident microbes are integral to every facet of our well-being. Given that animals have evolved with microbes since the very beginning, it shouldn’t be surprising that they impact our bodies in countless important ways,” says Hill.

“It’s an exciting time to be studying the microbiome as we’re starting to uncover many of the mechanisms that explain how microbes affect our physiology, and this knowledge can be used to develop new therapeutics and interventions. My work is just starting to scratch this surface and I hope to continue to find new ways that microbes impact pancreatic health,” she says.