Making Opioids Safer, One Patient at a Time

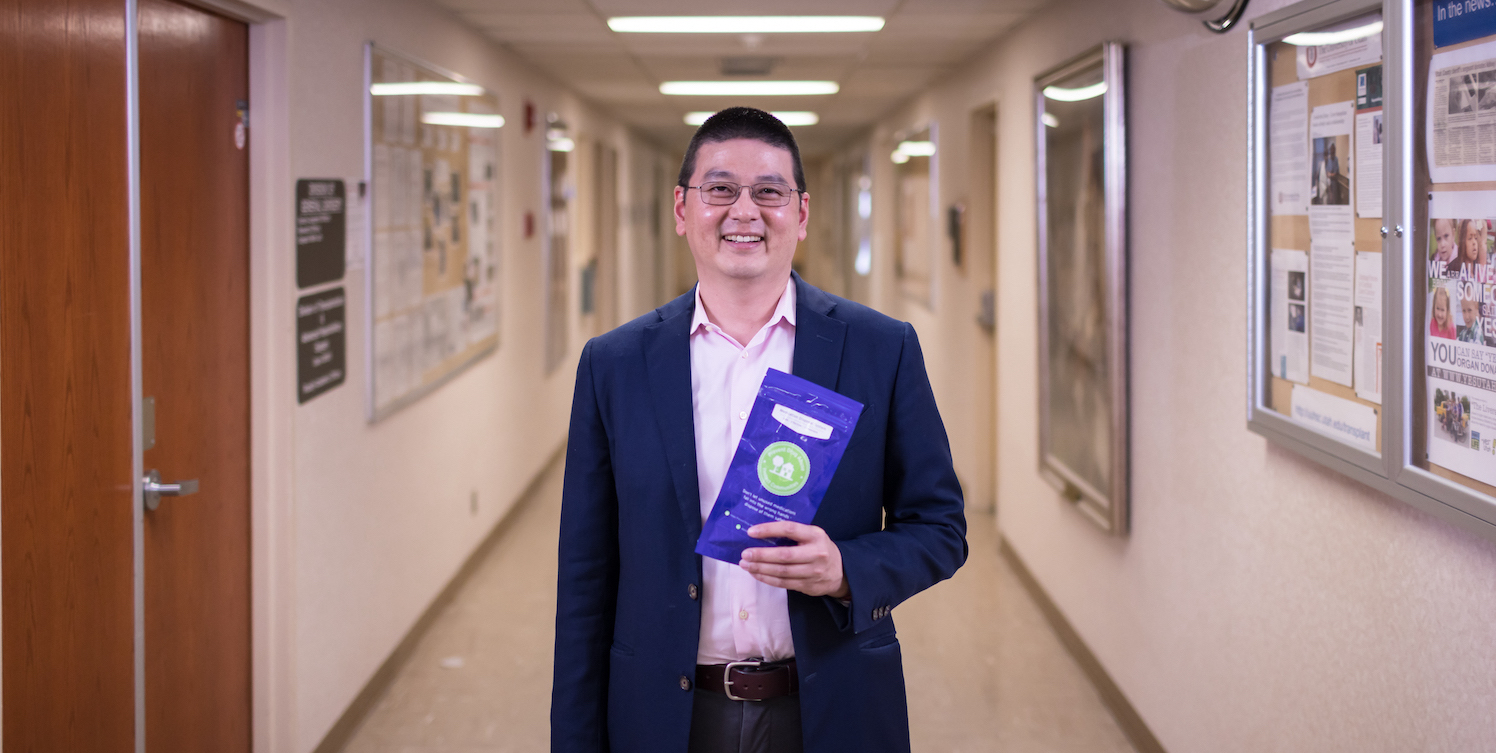

Two-thirds of patients who have leftover pills from an opioid prescription don't dispose of the drugs properly. Research by Lyen Huang, MD, MPH, shows that access to a new disposal kit reduces the risk of misuse and accidental overdose.

Author: Emma Penrod

Medicine cabinets across the country are filled with unwanted opioids. That’s because patients who have leftover pills from an opioid prescription don’t know what to do with them. In fact, two-thirds of patients who have leftover pills from an opioid prescription will not dispose of the drugs properly.

But Lyen Huang, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of surgery at the University of Utah Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine, doesn’t blame that on the patients.

“When I started this project five years ago, everyone rolled their eyes and said, ‘as surgeons, we’re not responsible for this,’” Huang says. “Patients want to do the right thing, but we have to make it easier."

When it comes to disposing of unused drugs, we make doing the right thing unnecessarily hard, Huang explains. Most patients know that flushing drugs down the toilet or throwing them in the trash can cause water and land resources to become contaminated.

But carving out time in busy life to figure out when and where the next community disposal event is a lot to ask. So instead, patients tuck pills away and promise to get around to it soon. That increases the risk of misuse and overdose.

A Doctor's Role

Huang believes that doctors, too, play a role in both prescribing and disposing of opioids. Surgeons like himself, he says, often provide patients with opioids to control pain. Research has found that roughly 6% of opioid-naïve patients will become chronic users after major surgical procedures. The risk of becoming a chronic opioid user among individuals with no history of surgery is less than half a percent.

Realizing that cutting opioids out of his practice wasn’t realistic, Huang began researching solutions. In 2020, University of Utah Health rolled out a new program based on his work that allows patients to safely dispose of unused opioids from the comfort of their own homes—which nearly doubled the odds that patients would dispose of any leftover medication.

“When I started this project five years ago, everyone rolled their eyes and said, ‘as surgeons, we’re not responsible for this,’” he says. “Patients want to do the right thing, but we have to make it easier. They may have known [how to dispose of unused medications], but it was inconvenient, it was time-consuming... and when we take away those barriers, people will step up and do the right thing.”

Drug Disposal History

Huang was already thinking about opioid disposal in 2017 when the Utah Attorney General received a donation of specialized opioid disposal kits—small pouches pre-filled with activated charcoal.

“If you have leftover medications, or medication you don’t use, you can put your medication in that bag, add water, and shake it up,” explains Nathan Hagen, director of community pharmacy services for U of U Health. “It deactivates the medication and [makes] it safe to throw in the regular garbage.”

The AG’s office was unsure what to do with the donation, but Huang’s team saw an opportunity. Over the next year, he and his colleagues used the donated bags to run a pilot study with 571 patients: 50 patients with opioid prescriptions received one of the home disposal kits, and the study team later followed up with a survey to determine what became of the opioids when the prescription was no longer needed. They found that 54.9% of the patients who received a disposal kit disposed of their leftover medication, compared to 34.8% of patients without one of the kits.

“The trial showed really good effectiveness, and the cost of these is really low,” Huang says. “At that point, we sat down and said, can we do this as part of our community responsibilities of reducing the impact of the opioids we’re prescribing?”

By August 2020, the team had the approval to begin providing disposal kits to any patient filling an opioid or benzodiazepine prescription in 13 U of U Health pharmacies scattered around Salt Lake Valley. Between August 2020 and May of last year, the university distributed more than 10,000 disposal bags or about 1,000 per month.

Pharmacy Collection Boxes

The new disposal kits aren’t the university’s first foray into drug disposal efforts. Six years ago, U of U Health installed collection boxes for unused medications in its pharmacy locations, allowing patients to drop off unused medications of all kinds at any time, no questions asked.

“It did not take very long for people to hear that we had it, and it picked up very quickly,” recalls Megan Lowe, pharmacy manager at Redwood Health Center. “It is highly used—and has been from the get-go.”

While some patients simply drop off a bottle or two of medication when they come in to pick up new prescription, Lowe says she has seen others bring in sacks or even boxes full of medications to dispose of while they’re cleaning house after an extended illness or death of a loved one.

Between 13 pharmacies, the university now collects about 600 pounds of prescription drugs per month, Hagen says.

The new drug disposal kits—which began distributing to many university pharmacies in August 2020—build on existing collection efforts with a more targeted approach, Huang says. The collection boxes are open to nearly any kind of medication, excluding certain hazards like syringes.

But the pouches ensure that the highest-risk medications, which typically represent a fraction of the drugs picked up in disposal boxes, are safely destroyed. They also make disposal easier for rural patients who may not make the trip back to university pharmacies on the Wasatch Front to dispose of old medications, Hagen says.

Essential Community Service

For Davis Moore, supervisor of the Greenwood Health Center pharmacy in Midvale, the university’s efforts to dispose of unused prescription medications represent an essential community service—part of what it means to practice medicine conscientiously.

“It’s worth it just to make sure that we give an option so people don’t have to pollute,” Moore says. “And so they don’t have accidental overdoses and poisonings.”

Yet Huang believes this work is only just beginning. The next steps, he says, are to begin work on the patient-provider relationship. Emerging research has shown that when patients worry about not having easy access to a doctor in times of need—or don’t believe their doctor will listen to them when they talk about their pain—patients are more likely to keep or share prescription opioids.

A Change in Perspective

Many doctors’ initial response to the opioid crisis was to crack down and restrict or reduce opioid prescriptions, Huang says. While more can be done to tailor the dose and number of pills prescribed to a specific patient’s situation, being excessively stingy about pain medication undermines the patient-provider relationship—and may actually encourage drug misuse.

The good news, Huang says, is that a growing number of medical practitioners are open to new ideas about managing opioids. Today, he hears fewer instances of “It’s the patient’s fault—they’re the ones using,” and more responsibility on the part of clinicians: “I’ve seen a lot of people come around to the idea of being stewards.”