A Leap of Faith

How a Finnish champion skier and a visionary Utah doctor brought an adaptive-recreation powerhouse to life

Author: Julia Lyon

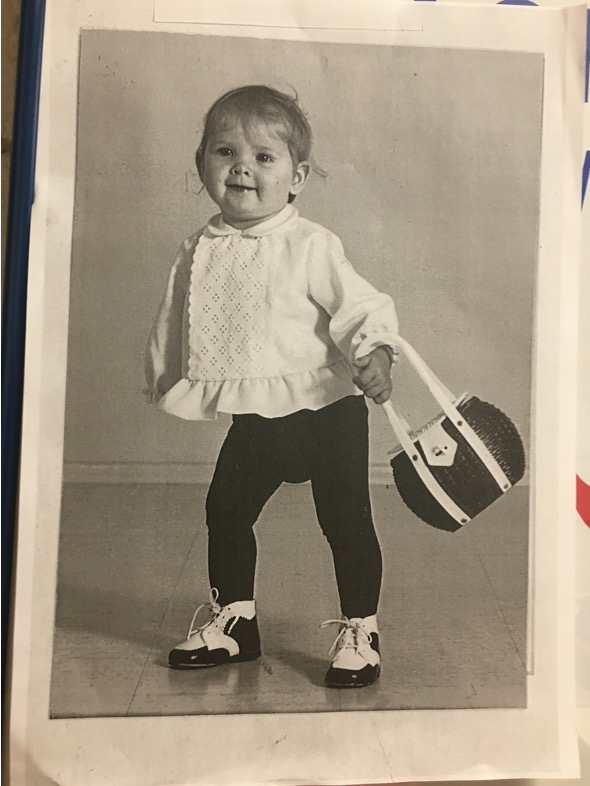

For Tanja Kari, growing up in Finland two hours from the Arctic Circle meant skiing, skating, biking, and climbing with her brothers in long periods of darkness—sometimes in the bitter cold.

“It didn't matter if it was 40 degrees below,” she remembered. “In those days, my mother had to beg to get us back into the house.”

Neither the weather, nor Kari having been born with a partial right arm could stop them. Kari’s mother treated the siblings as equals, believing her daughter should be as active as anyone else. Kari carried that belief with her throughout a career as a champion cross-country skier, and into Salt Lake City.

At the University of Utah, Kari teamed up with Jeffrey Rosenbluth, MD, a spinal cord injury rehabilitation specialist, to create an adaptive recreation program, which now serves more than 1,500 people along the Wasatch Front and beyond. Growing that program—Technology Recreation Access Independence Lifestyle Sports (TRAILS)—took the persistence and vision of both Kari and Rosenbluth, who shared the belief that participation in sports and exercise at the highest level of independence and performance should be available to everyone, no matter what their physical abilities are.

Had Kari not decided to chase a few gold medals, she and Rosenbluth might never have met.

Get your boots on

Growing up in Finland, Kari watched the Winter Olympics on her family’s old black and white TV and was inspired. She got up, went outside, and made her own race course and jumps. She and her brothers cleared a small frozen pond near their house for their hockey games.

“I wish I could go back to those times,” Kari said.

Even then, she was very competitive, trying to outrace schoolmates in running and skiing.

“I always wanted to win and most of the time I did. I beat the able-bodied guys,” she said. “I don’t remember ever facing anybody who said, ‘You are weird or you don’t have an arm.’ They walked away and said, ‘She’s going to beat us.’”

As she grew older and began competing against kids outside her small town, her confidence briefly wavered.

“What if they think I’m a weirdo?” Kari remembered thinking. “What if I’m not the best?”

Her no-nonsense mother told Kari to get her skis and boots, and to get going.

So, Kari skied. And skied. Most of the time, she was the best.

When Kari came to Salt Lake City in 2002 to compete in the Paralympic Winter Games, she wasn’t focused on anything other than her own races. She loved Utah’s tall mountains—so different from Finland’s hills and tundra. Once again, Kari beat the other skiers and took home three gold medals.

A few years after she decided to retire from competitive skiing, Kari was introduced to Rosenbluth who told her about his hopes for TRAILS, then in its infancy.

Kari, who had an M.S. in Sport Science from the University of Jyväskylä in Finland, shared Rosenbluth’s belief that adaptive recreation was, simply, recreation.

“We didn’t think this stuff we were doing was special,” Rosenbluth said, reflecting back on the beginnings of TRAILS. “Going for a bike ride shouldn’t be special. For anyone.”

It was 2005. Having lived in the sports world her whole life, the idea of harnessing that background to help people with disabilities strongly appealed to Kari. Rosenbluth asked her if she wanted to run TRAILS and she quickly accepted.

"This is very similar to running any kind of sports organization—the tasks that we have—but the receiving client and the population make this different,” she said. “And the meaning of this to me is much more. It can change lives. It can save someone’s life.”

Going rogue

While Kari was skiing to victory in Finland, Rosenbluth was skiing with people with spinal cord injuries in California. Then an undergraduate student at the University of California, San Diego, he volunteered with the adaptive ski program at Bear Mountain Resort where he saw firsthand how powerful it was for people with disabilities to get out on the snow. The advances in equipment and technology for this unique population excited him.

He stayed involved in the adaptive rec world after graduation and through medical school. During that time, the future doctor had a realization that would shape his career: For people with disabilities, being active and challenging themselves in new ways was rehabilitating in itself.

After completing his spinal cord injury medicine fellowship at the University of Washington, Rosenbluth landed at the University of Utah in 2001, where he saw how so much of patients’ time in the hospital was spent on body fundamentals like restoring bowel and bladder function. What so many patients also wanted was to restore a little bit of who they were.

“I think people have a self-identity,” he said, which for many revolves around a sport or hobby. “I’ve always felt if you want to follow rehabilitation to its furthest reaches you have to help people get back—all the way—to those things that were important to them.”

So, he planned to make an adaptive sports program a key focus in rehabilitation despite the fact "that it wasn’t widely supported here and at many other rehabilitation centers.”

Some rehabilitation programs see adaptive recreation as an “extra” while Rosenbluth believes it’s central to the patient’s quality of life.

Rosenbluth acknowledged metrics make it difficult to prove the value of a program like TRAILS. “It’s kind of a leap of faith that recreation will play a strong part in recovery after an injury or illness.”

But his certainty in this belief has never wavered. After all, he had seen the proof more than once as a young volunteer.

After a 2005 summer vacation left him feeling tired and weak, Rosenbluth noticed his face drooping as he shaved. Doctors quickly diagnosed him with Guillain-Barre syndrome, which is extremely rare. Rosenbluth grew weaker and had extensive paralysis. He was in the hospital for about three weeks.

Though he recovered, the experience gave him unique insight into his patients’ challenges and how they experience care.

Rosenbluth, who was leading the University of Utah Health spinal cord injury rehabilitation program, refused to let go of his vision. With a grant, a few handcycles, and no staff, TRAILS began—slowly.

The idea was brand new, so he had to work hard to explain his vision and to convince hospital staff to volunteer their time.

“It kind of felt rogue, but also amazing and I had a strong sense of where we were going,” Rosenbluth reflected. “And now, when I look back, it all makes sense.”

Doing It for the kids

After Kari became the first TRAILS employee, she built databases, planned events, and met with potential participants. For some athletes, it took a few phone calls over a few weeks to persuade. For others, it took years.

“This is not necessarily an easy population to find them and to convince them to do something,” she said.

Some patients, particularly those who had exceled at sports prior to their injuries, remained unwilling to see themselves as anything but skiers standing on skis—not someone whose injury forced them to sit down and ski in a new way.

The same skills that made Kari a champion athlete helped her convince participants to give TRAILS a chance.

“It’s absolutely total persistence,” said Rosenbluth. “There’s a gentleness to it and an aggressiveness to it also—I think she has a great sense of what people need.”

Persistence was something Kari undoubtedly needed with Wally Lee, who took years after his accident before he was ready to return to the sports that he loved.

It was a beautiful, sunny day in February 2002, when Lee lost control of his sled in Neffs Canyon, went off an embankment, and hit a tree. The impact broke his back.

Lee, an emergency room physician at University Of Utah Hospital at the time, told the paramedics to take him to his own hospital.

“Talk about being on both sides of the experience,” said Lee, now 57. “I knew what was happening.”

He had moved to Utah from California, in part, to be close to the mountains. Before his accident, he used to cross-country ski in Millcreek Canyon and explore the Wasatch on his backcountry skis.

The accident left him paralyzed from the waist down. It took seven years to get back on the snow.

“You’re already feeling sort of subhuman when you lose your ability to walk,” he said. "You feel like you’ve lost a part of your person. You don’t want to go out and do something that’s going to remind you … especially an activity that was such an enjoyable part of your life.”

Lee finally came to the conclusion that he could sit at home and never be active again or try something new.

“A lot of motivation was the kids,” he said. His daughter was going into high school. Lee remembered thinking, “She’s going to be gone and out of the house if I don’t suck it up and figure it out and get out there.”

At first, the clunky cross-country equipment owned by TRAILS did little to pique Lee’s interest. But Kari bought two light-weight frames from another Paralympic skier that helped change his mind. Rather than slogging along, Lee glided smoothly in his sit-ski. Thanks to Kari, his skis were always perfectly waxed to match the snow condition and temperature.

A fairy tale

At first, the program had very little equipment. The team quickly realized their three handcycles would have to be modified depending on the user’s needs. Kari, Rosenbluth, and an SCI team physical therapist, Sue Sandwick, met at Liberty Park after work with as many spinal cord injury patients as they could schedule to participate during the remaining daylight hours.

“People went crazy about it,” remembered Sandwick. “They were asking for more.”

As the sun set, they adjusted gear, switched handgrips, and scrambled for wrenches in the grass. The end of their day often arrived after dark.

“This is like a fairy tale,” Kari said, reflecting on those early days. “You know how good things start? This is how they start.”

No more free rides

Initially, TRAILS focused exclusively on the spinal cord injury community—Rosenbluth’s specialty—and the number of participants grew quickly.

First, there were 30, then 60 participants, and soon Kari was running a cycling program 15 to 20 hours a week, coordinating people based on equipment and staffing needs. Word of the program spread among the spinal cord injury community. Participants, who were proud to see so many people like themselves achieving what they’d thought to be impossible, informally mentored each other during cycling sessions.

TRAILS asked athletes what other sports should be added and started a downhill skiing program as grants funded more equipment.

Early on, a potential athlete with a very complex, high level spinal cord injury questioned Rosenbluth: “What are you going to do with me? Ski me down the hill? What is there for me?”

Rosenbluth and Kari didn’t want to build a program that just offered “rides.” They were determined to give people with complex disabilities a chance to be active and independent. That determination eventually led to the 2017 development of the TetraSki by the University of Utah Rehabilitation Research and Development Team. The groundbreaking technology allows skiers with no control over their legs, arms, or trunk to carve beautiful turns independently and to control their speed through a sip-and-puff breath system integrated into the ski.

Grants now fund free training and access to the TetraSki for adaptive sports programs across the country. The University of Utah also recently paid instructors to offer lessons and information about the specialized ski device at resorts throughout the U.S.

“Our ultimate goal is that everyone in the world who needs to or wants to use a TetraSki is in a reasonable distance from one,” Rosenbluth said.

Lina Nguyen hoped to be riding one this spring. TRAILS had helped the 27 year old do things she once thought impossible, many of which she’d never tried even before the car accident that left her a quadriplegic at 16.

“I can show others they can do it as long as they adapt to it,” said Nguyen, who is paralyzed from the chest down. “It helps normalize things in our lives.”

Over the years, the number of TRAILS sports has continued to grow—along with the variety of complex disabilities of the participants. Partnerships with other community organizations from The Utah Nordic Alliance to the Salt Lake City Marathon provide athletes with more opportunities to compete as well as more spectators and fans during races.

Now the program offers nearly daily opportunities to recreate. In addition to skiing and cycling, athletes and their family members can swim, play tennis, shoot bullets, and sail boats—depending on the time of year. All of it is free.

Nguyen is one of the participants who has sampled a wide variety of sports including skiing, boating, cycling, and shooting at the gun range. With limited function in her arms, shoulders, and wrists, she can still hit a button and make a bullet fly.

Kari is determined to find a solution to every challenge, from strategizing how to get someone in a wheelchair across half a mile of sand and mud to starting a cross country ski race in a location so the athletes don’t have to start the course by flying straight downhill.

“With the right attitude, you figure it out,” she said.

Today, TRAILS is fully integrated into the University of Utah rehabilitation program. Kari meets with patients before they leave the hospital and explains the recreation opportunities. “She’s making it the best experience possible,” Lee said.

Rosenbluth’s vision has become a reality. “Even if they weren’t ready to see themselves getting involved in recreation again, they couldn’t really go home and say, for example, ’I’m never going to ski again.’ They would know that wasn’t true,” Rosenbluth said. “We want to make sure people know we are here when they are ready.”

Feeling the burn

Each person who TRAILS works with comes with a clinical history and complex diagnosis, along with ambitions and dreams.

Two years after a 2012 rappelling accident left Brittany Fisher Frank paralyzed from the waist down, she was ready to be active again. She had finished student teaching, moved closer to Salt Lake City, and was finally in a better place mentally.

Before falling about 80 feet down the side of a cliff, landing on her feet, and fracturing her T12 vertebra, Frank had run for the Utah State University team. She used to run as far as she could, loving the burn in her lungs and legs. Frank had quickly discovered adaptive downhill skiing lacked the cardio high she craved.

Kari knew that cross-country skiing could be the antidote. It’s a sport that TRAILS has a lot of experience in, said Lee. “Right now we have the most cross country equipment and the best cross country equipment I’d say anywhere in the West.”

“I told Brittany it’s probably the only sport that can make you feel exactly like cross country running made you feel,” Kari said. “It’s a brutal sport. The more you do it, the more you exercise and train, the easier it is.”

She was right.

“It was the first time I’d felt that burning in my lungs since I’d been injured over two years before,” Frank recalled.

Frank’s arms grew stronger as she learned to propel herself with her ski poles while sitting in a bucket seat clamped down on skis. In the summer, she could use a mountain board with wheels on the road and get an equivalent exercise high. The athlete shone in her new sport, competing in the North American Nordic Skiing Championships in 2015 and 2016.

Frank, who is now the mother of a 2 year old, has stepped back from competition. But she remains active in TRAILS and credits the program for helping restore her confidence in herself.

“I feel very fortunate,” she said. “You realize how few and far between these programs are especially with people as good as Tanja. Tanja is not only persistent and caring, but she’s a powerhouse there. I don’t think the program would have come together as strongly without her.”

The world stops

Both Lee and Frank were planning to train with TRAILS for the Salt Lake City Marathon when the COVID-19 virus shut down outpatient services at the University of Utah in March, forcing TRAILS programming to a halt.

Kari was relieved the program wouldn’t put her vulnerable athletes in danger.

A respiratory infection, which often results from the novel coronavirus, could be fatal for them. Many have weakened immune systems and inadequate diaphragm and abdominal muscle strength. That means they can’t cough very well.

“So if you can’t cough you’re going to succumb to these things faster,” Rosenbluth said.

Across the globe, millions of people were washing their hands more carefully. But some TRAILS participants struggled to keep themselves and their wheelchair clean—even before the pandemic.

If their hands didn’t work normally, washing them was hugely problematic. And finding hand sanitizer and disinfecting wipes had become almost impossible whether you were able-bodied or not.

Frank, who is in a wheelchair, tried to remember to wipe down her wheels.

"It’s just one more point of contact I forget about in the store,” said the 29-year-old.

Frank had hoped to reconnect with TRAILS members in the spring. Now COVID-19 had forced her to adapt once again—along with so many across the world.

“It took me a long time to find my new normal with my wheelchair—now I’m still struggling,” she said. “It’s finding your new normal again and that’s hard.”

Lee, who is also in a wheelchair, felt a sense of loss as resorts across Utah closed early due to the virus.

“For alpine skiing, that’s it without a chair lift,” Lee said. He had been able to do some cross-country skiing on his own, but it hadn’t been easy. The retired doctor knew that when the snow melted he could get out again on his adaptive mountain bike. He was lucky.

Until then, he was primarily staying home, staying safe.

“I don’t want to be a health burden to my kids if I get sick,” he said.

A virtual dance

So, TRAILS tried to make things a little bit more normal. A little bit better.

By April, the program was offering a virtual version of their “Get Wild” dance exercise class and yoga several days a week.

The athletes—many of whom were extremely isolated—loved seeing each other, even if only on a screen.

Kari and her staff distributed handcycles to participants’ homes so interested athletes could do virtual spin classes run by TRAILS. Staff took safety measures, wearing protective gear and social distancing while dropping off the equipment on athletes’ front porches. Before they left, they thoroughly disinfected the equipment.

They delivered hand sanitizer manufactured by a brewery in Ogden to those participants who needed it along with N95 masks.

Sandwick, the physical therapist who has been a consistent team member since the program’s early days, quickly organized an outreach crew of University of Utah Health staff and students to check in on every participant by phone. The contacts have been enthusiastically welcomed by the TRAILS participants, some of whom were feeling lonely, frightened, and isolated, and were still trying to find solutions to their everyday dilemmas. Sandwick helped set up grocery deliveries, connect participants with important community resources, as well as to obtain necessary medical supplies and have them delivered.

“This population is definitely at high risk,” she said. “So we do not want them out in the community unnecessarily during this time.”

Even when social-distancing restrictions lifted, Rosenbluth anticipated that TRAILS would stagger participants to try and minimize any potential exposure.

The program would maintain its large off-campus garage even as the new Craig H. Neilsen Rehabilitation Hospital opened in late May 2020. The TRAILS space has rows of adaptive bikes, skis, and other sports gear along with the tools to adjust equipment to each athlete’s needs. It normally hosts exercise classes and education events—and will again one day.

In the meantime, some TRAILS virtual classes will be streamed out of one of the high-tech rooms in the new hospital. The plan for Kari to introduce Tetra technology across the world will have to wait as the uncertainty about COVID-19 continues.

Kari said her job has been a privilege. She has helped people become healthier, find community, and get more involved in sports.

“It goes back to the reason why I’ve been in this so many years,” she said. “Through this program some people have said, ‘Thank heavens this accident happened to me, because I’m living a much better life than I did before.'”

Photo of Tanja Kari in front of Utah State Capitol building by Charlie Ehlert.