Unadorned Heroes

For Christopher Duncan, his amputee patients’ emotional healing is as important as the physical and functional.

Author: Heather May

Thirty minutes after the doctor’s appointment started, Christopher Duncan finally asks his patient about his leg.

On the surface, the right leg—really, the absence of it—is why the Salt Lake City man is at the University of Utah’s Physical Medicine Rehabilitation Clinic. The early 40s man had it amputated above the knee two years ago, following a work accident. He’s here on a recent morning for follow-up care with Duncan, a physical medicine and rehabilitation doctor.

But first, Duncan wants to know the patient's story before the accident, about his family, his work, his hobbies.

“My job is to try to get you to feel like who you were before this happened and to make you feel whole again, to do all the things you want to do, physically, functionally,” Duncan tells him. “That means emotionally, that means your job, that means your relationships."

A space develops between where a person was before their amputation—physically and mentally—and where they are after. Duncan says his job is to bridge that distance as best he can. It requires a holistic approach to treating patients. Besides preparing patients for prosthetics, the University of Utah Amputee Program, in the Neilsen Physical Rehabilitation Hospital, treats residual limb and phantom pain, addresses joint mobility, weight management and skin care; trains patients how to fit their artificial limbs and perform daily activities with them; and offers referrals to physical therapy and counseling for anxiety and depression.

Duncan considers himself a facilitator for the hundreds of amputee patients seen each year at the U. In Utah, the vast majority of amputations are performed on men and on their lower extremities, ranging from toes and feet, to above-knee amputations. The number of amputations is growing—it was 739 in 2014 in Utah—and is expected to keep climbing due to the rising rates of diabetes and vascular disease, which nationally is the top cause of amputations, followed by trauma, ranging from workplace accidents to infections.

“It’s important to see the whole person and see what they want,” Duncan explains outside the patient's room. “That’s everything I ask in my appointments—'What do you want?’—in nuanced ways.”

The answer depends on the person: Despite it being more cumbersome to wear and use, one patient wanted an artificial leg that would resemble the shape of her other leg because it was important to her to look natural when she went to church. Another wanted his artificial hand to look unambiguously artificial as a projection of personal style while at the same time celebrating his alma mater—it was 3-D printed with a University of Utah "U" logo.

Distributing the Future

Duncan grew up tinkering. His dad was a builder and his mother a kitchen designer. Duncan taught himself computer-aided design and minor electrical engineering, building robots with his brother. During medical school, he said he was overcome considering the tragedies that can happen to people through no fault of their own. He gravitated toward rehabilitation medicine because it allowed him to offer patients concrete solutions.

“I think many physicians are frustrated engineers. … There’s pressure for us to see suffering and misfortune and not be able to fix it.”

That frustration led Duncan to combine his engineering and medical talents to work for amputees. About half of patients who have lost parts of their arms abandon their prosthetic because it isn’t well made or it doesn’t work for them, he says. They most often end up using a stainless-steel hook. That’s not good enough, Duncan says. “I have a female patient who uses two hooks. She has a 3-year-old daughter. She cannot change her diaper. These life tasks are absolutely critical for her to able to do and they can’t be done.”

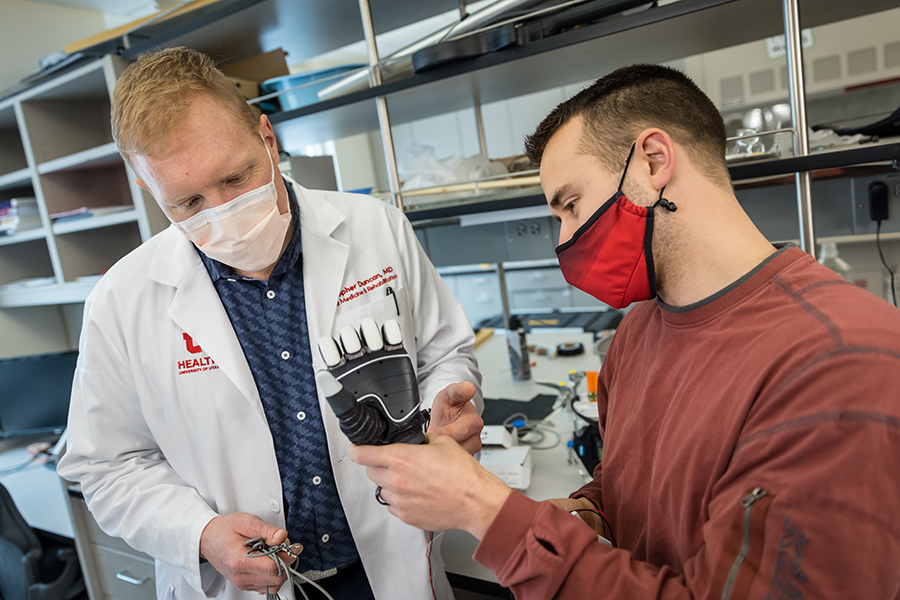

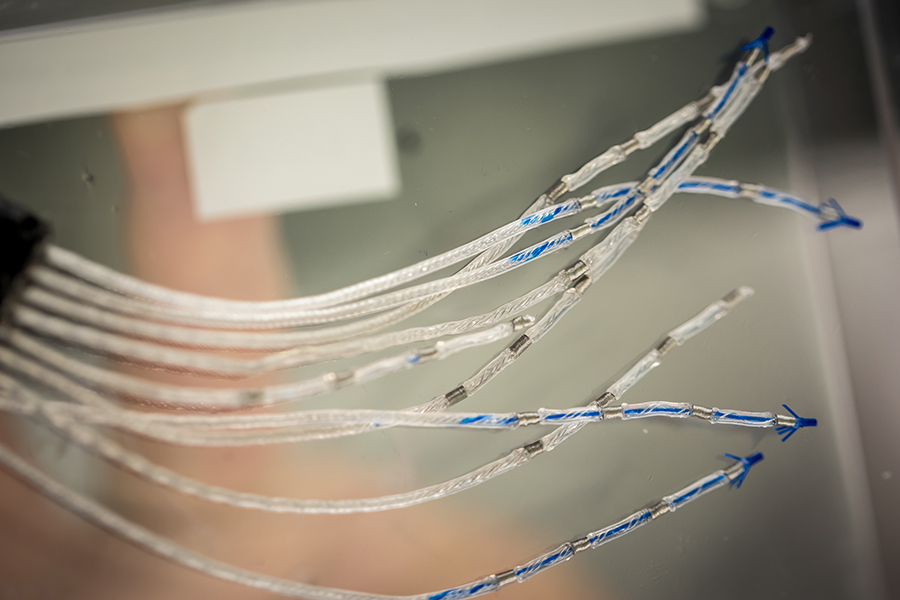

Duncan is part of a multidisciplinary team, through the U Center for Neural Interfaces, which has designed a prosthetic arm that allows the wearer to control it through their thoughts. The volunteers in the experimental program can pick up and manipulate objects and report they can feel sensation again. Duncan wants patients to not only be able to perform mechanical tasks with a prosthetic but also express themselves—reassure their children, grasp a loved one’s hand, scratch their face, for example. “It’s relaying emotion and sense of self through our hand gestures. We do that all the time,” Duncan says. But, “We don’t have prosthetics that can move with the gracefulness that our normal hands move with.”

The new Neilsen Physical Rehabilitation Hospital allows a closer alignment of researchers, scientists, clinicians and therapists to address limb loss as a team and create better tools and outcomes for patients. “That is the true promise of this building because it brings us all together,” Duncan says.

His favorite quote hangs on the wall of his office: “The future is already here. It’s just not evenly distributed yet,” attributed to the science fiction writer William Gibson. It reminds Duncan to strive to restore what he can of his patients’ former lives, or to get them the best tools available.

“Fate is so capricious. People who end up in a car accident—was it them driving, were they swerving? Most of the time, no. The little girl who gets a cut on her leg and then gets septic. Or the lady who goes in for a core biopsy on a possible nodule on the breast and gets septic after that and loses all four limbs. She’s one of my patients. I think to myself, ‘That’s not fair. What can I do to re-establish a level playing field in some ways?’”

“Do it for you”

Travis and Carma Robinson say there is no returning to their former life when Travis worked as a mechanic and they could go on vacations and hunt and hike. Robinson lost both legs—one below his knee and the other above the knee—after they were pinned under a train car while he was working at Kennecott Copper Refinery in 2016.

The 34 year-old sees Duncan for skin care, sweating, and steroid injections in his left lower limb to treat phantom pain. Though he has no feet, Robinson says the pain he feels is like a cigarette lighter being burnt between two of his toes. Duncan also prescribed medicine for anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Duncan asks Robinson what he can do to help him return to life before the accident. And while Robinson says his life will never be the same, he praises Duncan—whom he now considers a friend—for even asking. “He’s the best doctor I’ve ever had. Dr. Duncan actually gives a damn and sits and listens to you,” Robinson says. “He knows me, he knows my wife. He knows my son.”

It was Duncan’s voice Robinson heard when he tried to walk for the first time on prosthetic legs, and Carma Robinson credits the doctor for motivating her husband to try.

“I didn’t want to,” Robinson said of walking again. “The pain was just so bad. The fear of the unknown. It’s like the man on the moon.”

He and Carma recall Duncan not giving up. “I remember his words ringing in my ear,” Robinson says. “‘I want you to at least try and give 100% and if you don’t, you’ll be failing yourself. Do it for you.’”

Duncan recruited Robinson to test out a prototype prosthetic knee, through the U Center for Neural Interfaces as part of a study for the Department of Defense. The idea is that signals from his brain would make the leg go up and down stairs. “If my body can be used for research for something that can help [veterans] … to make their life easier, I say go for it,” Robinson says.

“Travis has been a wonderful patient to care for,” Duncan says. After such a devastating accident, Duncan has watched Robinson relearn how to walk “as part machine, leave the house and rejoin the community,” he continues. “Travis exemplifies that my patients are the true heroes. I am there to shine a light on what’s possible, motivate them that it’s worth doing, and solve the inevitable problems as they arise.” While it’s painfully apparent to Duncan that existing prosthetic technology has far to go in terms of improving patients’ lives, he nevertheless strives to both develop and collaborate with scientists and other colleagues to show the world what’s possible in prosthetic development.

Triumph Over Challenges

Duncan has created a series of webinars for people with amputations, covering phantom limb pain, nutrition and emotional health. His closing message in one on the mechanics of prosthetics stands out: The most successful people he sees with amputations are those who can turn the corner from seeing it as a catastrophe to viewing it as a new chapter in their lives. They pause and consider: “’Who am I? What is valuable to me? What do I want to do with myself?’” he says.

Duncan can point to Steven Conant as a model: The now-64-year-old lost both hands below the elbows and both legs below the knees two years ago after a workplace accident in which he was zapped with 70,000 volts of electricity. The outdoorsman who loves to ski, climb and hike now needs an aide to start the coffee in the morning and help him put on his prosthetic arms so he can attach his legs. Conant finds it amazing that the electricity didn’t affect his circulatory and nervous systems. And while Duncan wants to help him ski again, Conant focuses on the walking he does around his neighborhood and to his local pub to meet friends, and the short hikes he can do in Big and Little Cottonwood canyons.

“I decided in the beginning I was going to be the strongest and best I can be. I’m doing as good as I possibly can,” Conant says. Duncan agrees. He tells Conant he is doing better than much younger patients, and he has asked Conant to visit new patients who have just had surgery, to show them life continues.

“The path to becoming a true human being is a long path, you just gotta work on it,” Conant says. “I have no long-term goals. I think short-term every day. I put on my legs, put on my arms. Eat breakfast, get out the door for walking. That’s half a day. I take things one step at a time. I’m just taking my time and figuring out how to live with all these prosthetics.”

Every time Duncan hears Conant’s buoyant, booming tones in the clinic, he can’t help but smile at his expectation that his patient will yet again surprise him with a new challenge and news of a triumph. “When I first met him, he was confined to a wheelchair with amputations of both lower legs and at the forearm; his aide did everything for him,” Duncan recalls. “His therapists and prosthetists have done an amazing job of training him. Now he does all the usual stuff we take for granted: dresses, brushes his teeth, prepares meals, walks to the store and impresses nearly everyone he meets with his independence. He has a spirit that is indominable. He’s climbed countless mountains but to watch him thrive after a brush with death and loss of his hands and feet is a true honor.”

Patients leave a visit with Duncan feeling something that the original accident or infection took away from them: optimism.

"I want to offer people the best life I can, knowing full well there may not be a cure,” says Duncan. “I feel a huge obligation to offer these people a better life."

Photos by Charlie Ehlert

###