Deadly Cocktail

A new study reveals the Utah opioid epidemic death toll includes an alarming number of new moms.

Author: Stephen Dark

Stephanie lay in the Salt Lake County jail bunk bed and thought, “Everything would be better if I just died.”

She was a burden to everyone she knew, and no one could trust her. She’d pawned her mom’s wedding ring, stolen her sister’s jewelry. There was nothing she wouldn’t do--or steal--to stave off the desperation, the seizures, and overwhelming sickness that assaulted her body every time she was “jonesing” for heroin. (Stephanie requested anonymity to share her story.)

Sexually molested and raped as a child, she’d started using drugs when she was 13, while growing up in Springville and Provo. It wasn’t until she went to prison for drug-related crimes that she decided rather than dying, she wanted to change. “Me going to prison is what saved my life,” says the 37-year-old. She took up healthy habits, running every day in the women’s circular yard.

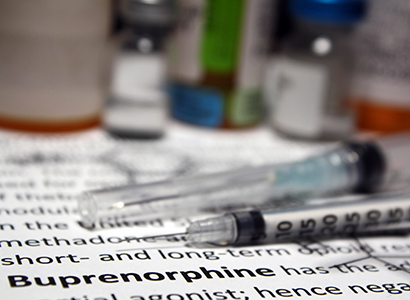

But paroling from prison was one thing, transitioning back into society another. After a stint in the Orange Street halfway house for women, she lived in a tiny apartment with only a blanket and pillow--no food, no TV, or phone--while working as a server in a Mexican restaurant. She met her subsequent husband on Trax. He was working on his recovery from addiction using Suboxone (buprenorphine/naloxone), medication used in opioid replacement therapy. The couple relapsed and lived off scamming cash from stores with discarded receipts.

Two more stints in prison and Stephanie and her partner couldn’t figure out how to turn their lives around. They would buy Suboxone from a dealer on the street, but when she found herself pregnant, she was terrified the state would take her baby away. Her doctor told her to aggressively taper the medication, but that only led to her craving heroin.

Stephanie called Marcela Smid, M.D., the medical director of University of Utah Health’s Substance Use in Pregnancy Recovery Addiction Dependence (SUPeRAD), a specialty prenatal clinic for women with substance use issues. “I need to get off this,” she told Smid.

“Don’t do anything,” Smid pleaded with her. “Stay on it. You’re stable on the medication and that is the most important thing you can do for you and your baby.”

Fast forward 18 months and Stephanie has now been on the same dose of Suboxone for three years. Her one-year old scampers around the living room of her sparsely decorated Sandy home, while her husband is at work. “It’s sad,” she says. “There’s not a lot of help,” for pregnant women who are frightened of relapsing if they go off the treatment medication.

While many providers and patients may view methadone or buprenorphine, two types of medications used to treat people with opioid use disorder, as a drug they need to be weaned off, Smid vehemently disagrees. Treating mothers helps to stabilize them and leads to the best outcomes for mother and infant.

“Addiction has been constructed as a social problem,” Smid says. “Medicine is catching up that it’s truly a life-threatening, chronic medical condition.”

The cost of that mistaken perception is evident in a study that Smid has just published entitled, Pregnancy-Associated Death in Utah: Contribution of Drug-Induced Deaths. It highlights the unrecognized price Utah’s mothers are paying in the midst of the state’s opioid epidemic. Mothers who have a history of substance use disorders often relapse in the first year after childbirth. In total 35 Utah women fatally overdosed on drugs (74% were from opioids), between 2005 and 2014, making drug-induced deaths the top cause of pregnancy-associated deaths in the state. The vast majority (80%) of deaths occurred in the late postpartum period, between 43 days and one year after the birth, after most women have had their one postpartum check.

Utah has long been in the grip of an opioid epidemic, from 2013 to 2015 ranking seventh in the U.S. for overdose deaths. It also has the highest rate of any state in the nation, at 42 percent, of pregnant women insured by Medicaid prescribed opioids, according to 2007 data.

If more postpartum women are not to be lost to drugs, Smid urges that deep changes need to be wrought in terms of both public perception and treatment. “We have a huge problem,” Smid says. “Our moms are dying in Utah, a state which says it values family above all else.”

Rethinking addiction

Societal norms may demand complete abstinence from mothers with substance use history to ensure a child born free of addiction. According to Smid, women with substance use issues do try to stop drug use during pregnancy. “Reproductive age women who do drugs, for whatever reason, when they get pregnant, they stop or decrease substance use when pregnant, but once they have their babies, many relapse.”

OBGYN providers generally see mothers 1–2 times within the six weeks after the birth. “Six months in and the baby is still screaming, and it takes a toll on moms,” says Smid, in terms of the long-term follow-up with moms. And from the provider perspective, "many don’t know the mom was doing drugs or had a history or was in remission when pregnant because maybe they didn’t ask and the mom didn’t disclose.”

While the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists now recommends ongoing postpartum or “fourth trimester care” rather than the post-birth single visit, the lack of providers nationwide versed in pregnancy and addiction is disturbing. There are only about four double-boarded maternal fetal medicine specialists who are also addiction medicine boarded in the U.S. says Smid, and she’s one of the four. “We don’t have that many people truly focused on pregnant and postpartum moms with addiction, which is incredible since it’s one of our most common conditions. It’s more common than type 1 diabetes.”

Smid finds parallels between opioid addiction and diabetes instructive. In both cases, she says 10 to 20 percent of patients with chronic diabetes or opioid use disorder successfully come off their meds. “The vast majority need medication to stabilize their brain. Their bodies lack natural endorphins, or the circuitry is altered so much that natural production isn’t enough to make them stable.”

Yet none of the women in the study were on methadone or buprenorphine to treat opioid addiction. Smid argues that postpartum moms with opioid use disorder history should stay on their medications, stay in therapy, and not taper off, something that even patients have been conditioned to expect.

“Do not think about tapering until kids are at least a year old,” Smid says. “Sometimes you don’t ever. Tapering may never be an option for you. You have a chronic life-threatening condition. Your brain may just need it.” She argues that since providers do not typically require patients to taper their diabetes medication, why force them to taper their medications for opioid addiction? “If more people thought about addiction like diabetes, we’d be in a better place. The vast majority of people need to be on medication for the rest of their lives.”

Missed opportunities

When Smid would ask patients about their first time on drugs many would say it was when they first felt normal, even happy, like they had emotions like everyone else. “It’s the first time it went from grey to color,” she says. “Your brain doesn’t make enough dopamine. You’ve added a substance that makes you feel great. That’s why it’s called ‘chasing the dragon.’ You want that feeling back.”

Patients are at a moderate or high risk of developing addiction depending on their genes. “Most of our patients have family history of addiction that is deep on both sides,” Smid says. “You get exposure to drugs, you experiment with drugs, and if you have that physiology you’re throwing a match into kindling.”

The study also highlights how society’s traditional view of people with addictions as shuffling derelicts strung out on the street is far from accurate. “People look at addicts and think they’re living on the streets, popping from one motel room to another,” Stephanie says.

While women on State Street, North Temple, and Pioneer Park, living chaotic lives trading sex for drugs, are the most visible example of addiction, they are the minority in terms of reproductive-age women using opioids, Smid says. “The majority of the moms live in houses, they look like the moms in the mommy group. They live in cul-de-sacs, they work, they keep their jobs.”

More than half of women who died in Smid’s study were sent home with their babies, Stephanie says, who read the study at University of Utah Health public affairs office’s request. “You don’t get sent home if the hospital or state think there’s a problem.” Which means, Stephanie says, that women are either not being screened for addiction and other histories, or are hiding them from their providers.

All that said, Smid notes, Division of Child and Family Services does a full assessment “and determines safety for mom and baby. The perception is that the state takes your baby if you do drugs. That’s not always the case.”

Postmortem, Smid found, providers didn’t know their patients had a history of overdose, substance use, and suicide attempts. “We’re not systematically asking every mom. We might ask the mom in Pioneer Park, but do you ask the Cottonwood Heights mom?” Sometimes providers do not ask their patients, because they don’t know what to do, Smid continues. "We have to train our providers in perinatal addiction care. They’re not automatically screening for substance use, mental health conditions and that’s a huge missed opportunity for us as providers to intervene and prevent these deaths. The system also needs to be able to respond to moms and have women-centered treatment facilities where moms can enter treatment with their children.”

The study details numerous examples of other missed opportunities to identify pregnant women with drug use history in the system. A quarter of the women had a prior history of overdosing, yet none of them had had counseling regarding preventing overdose or a prescription for Narcan (Naloxone). Despite mental health and drug misuse, most of the women had not received mental health or drug treatment.

The lack of screening for drug history is about to change. Smid has been training clinicians at U of U Health to implement the National Institute on Drug Abuse Quick Screen. The screening means providers, through a series of questions about alcohol, cigarette, and drug use, can both learn more about the patient and broach the potentially sensitive topic of prescription and opioid drug misuse. She and the U of U Health team are working to roll-out system-wide screening for every pregnant woman.

Stephanie underscores how life-changing long-term treatment and recovery is. “This is like my fifteenth chance and I’m very grateful where I am right now,” she says. “I’m in a better place than I have been in my life since I was 10 years old.”

Photo of Dr. Smid by Corrin Rausch, ARUP.