Author: William Sorensen

Most Utah Jazz fans who sit right behind the bench think of the players as superstars. For two University of Utah Health professors, however, the players are, in a way, not so special.

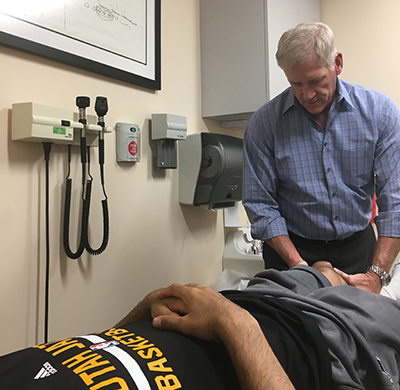

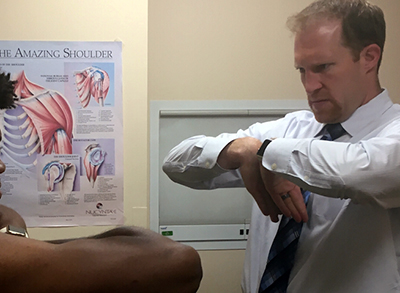

Travis Maak, MD, and David Petron, MD, both Associate Professors in the Department of Orthopaedics think of Utah’s NBA players as human beings first—and superstars second. That’s because they know the Jazz athletes almost as well as their teammates do.

Petron is Chief Medical Officer and Head Medical Team Physician for the Utah Jazz, while Maak serves as Head Orthopaedic Team Physician for the team. The doctors attend every home game, and during playoff season, they travel with the team to attend games on the road.

At Vivint Smart Home Arena, Maak and Petron sit a couple rows behind the Jazz bench, allowing them quick access to the players for treating injuries caused by a bad fall or collision during a game. But the physicians have responsibilities that stretch beyond game time. They are charged with maintaining the overall health of the team and of the entire Jazz organization.

“We care for players, administration, other medical staff, trainers, performance coaches, and more,” Petron says. “It’s a large group that we care for year-round.” Maak adds, “And their families and kids. We utilize folks from Moran for the ophthalmologic perspective, and we use the dental school, too. We have neurologists working with us. A lot of families have utilized OB/GYN services for labor and delivery. It really is a comprehensive care team that’s delivered.”

Expertise in All Areas

“Travis and I are on the front end of things,” Petron says, “but it’s our job to put together a network of the most highly skilled physicians within U of U Health, in every sub-specialty. Frankly, that’s part of the reason the Jazz chose us five years ago—they wanted expertise in all areas.”

When both men are in place, how do they split duties? Petron’s specialty is sports medicine, while Maak is a sports medicine orthopedic surgeon. “There’s a huge amount of crossover with what Dave and I do on the non-surgical side,” Maak says. “As far as specific differentiation, when it comes to spine and neurological stuff, there’s no question that Dave is far better at that, so I defer to him. Regarding extremity injuries, we kind of collaborate. And on the surgical side, that’s me.”

How well do big-name, highly paid professional athletes follow doctors’ orders? After a slight guffaw at the question, Petron says that actually, believe it or not, the players are very compliant. “We’re amazed at how professional these athletes are on and off the court. They really take care of their bodies. They listen to the training staff, who are working with them day to day.”

Maak adds, “Athletes understand we’re aligned with them and they understand that if they follow what we specifically ask them to do they’re more likely to stay well. The Jazz have a wonderful organization and their relationship with the university is similarly wonderful. The players understand that. They basically defer to us and do what we ask them to do. There’s a lot of responsibility that comes with that. These players, they’re somewhat of a captive audience. They’re at a professional level, and obviously, they are people with agents watching out for them. A complexity exists there.”

The professors don’t find treating athletes much different than their 8 to 5 jobs. “Players are patients,” Petron says. “Really, an injury is an injury that we need to treat, so we treat the athletes as patients first and as players second. We always look at them as a patient and consider what’s the best long-term care for them. Part of our job is stratifying risk for the athlete in returning to play, and one of our challenges is evaluating athletes for potential of future injury risk.”

Playing Through Pain?

Are professional athletes able to withstand pain better than patients who are basically “Weekend Warriors”? According to Maak, “Players, by definition, play in pain. With very few exceptions, they have a rigorous schedule that extends from September until May. And they’re playing two, three, sometimes four games a week in addition to practices. They’re always playing through injuries. The public doesn’t understand, really, that players are always beat up.”

“One of our jobs,” Petron adds, “is to evaluate that and determine if it is safe for them to play with pain. Are they causing further injury or potential permanent injury? Is it safe to play through some of that pain? “

Do athletes with stronger-than-average bodies heal faster? And do they expect to heal faster? Both physicians say yes. “But so does everyone else who’s watching them play,” Maak says. “Biology is what it is. The human body’s going to heal at a rate that’s consistent with a person’s age and body profile and the injury. You can’t necessarily advance biology. However, they are at the pinnacle of health. These guys take care of their bodies, so they maximize their ability to heal within the constraints that exist in the human body.” Petron points out the high level of visibility that goes into their role with the Utah Jazz. “Part of our job, when a player is injured, fans, coaches, everyone wants to know how soon they’ll be back,” he says. “Sometimes we can give an accurate timetable; other times we just have to see how the injuries play out.”

Lessons from Academia

The Jazz job does come with added pressures, due to the fact that Petron and Maak are physicians who make medical decisions in the spotlight. With a $1.4 billion sports organization closely looking on, plus a huge, involved fan base, medical calls might be questioned. There’s inevitably going to be second-guessing.

A job on campus has him steeled for that, Maak says. “In academia, we’re constantly second-guessed anyway. That’s the beautiful thing about being in academia. It stimulates thought; it stimulates discussion. If you’re a prideful person and are unwilling to have your opinion or concepts second-guessed, you probably shouldn’t be in academics anyway. Standing on podiums and giving presentations subjects you to a lot of criticisms—especially in the surgical world. It stimulates improvement, and that also extends to the professional world. If you approach professional athletes in a manner that you do for your regular patients, the outcome will be excellent. You try not to be fancy; you try not to do anything differently. You treat them just like you would treat any other patient and you try to give them the care you would give to a normal patient. Ultimately, that’s always the right answer. If you try to do something different and switch it because it’s an NBA basketball player, the outcome is not better, it’s usually worse.”

Seeing the Jazz stars up close and personal, throughout the year, in winning and losing situations, when they’re carefree or in terrible pain, are the players as warm and cool as they seem to outside observers?

“Yes,” Petron says. “They are amazing people.”

Even better, U of U Health doctors Travis Maak and David Petron enjoy a professional satisfaction often denied regular physicians: They get to see their patients perform outside of the office.