Author: Stacy W. Kish

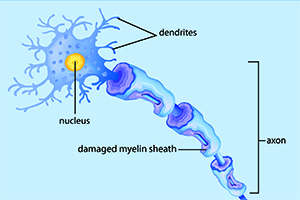

When you fall and scrape your knee, the injured tissue forms a red bump or lesion. Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an unpredictable autoimmune disease, characterized by lesions in the brain. These lesions, like the scrape on your knee, result from tissue injured as the overactive immune system degrades the myelin sheath surrounding the nerve fibers in the brain, spinal cord, and optic nerves.

Researchers at University of Utah Health studied brain biopsies of MS patients and identified 29 microbes from 11 different phyla within the tissue. This approach offers a new way to study this disease. The results are available online in the February 4 issue of Scientific Reports.

The researchers identified microbial remnants from brain tissue taken from the 12 MS patients and 15 controls. Because a brain biopsy is not a common procedure, the researchers used biopsies from epilepsy patients to represent normal brain material. They sequenced all the specimens to ‘put a name to a face.’

“We found the MS lesions were dirtier than the controls,” said John Kriesel, MD, assistant professor in Internal Medicine at U of U Health. “We are not just saying microbes are there, we are naming names.”

While the authors found some overlap between the MS and control samples, most of the MS brain samples were associated their own distinct set of microbial sequences. The following organisms were the most overrepresented in the MS lesions: Nitrosospira, Atopobium, Fusobacterium, and Aggregatibacter, and the fungus Ustilago.

While most of MS samples were enriched in microbial sequences, the researchers could not associate a single microbe or collection of microbes with all of the samples. Most of the MS microbes obtained from the MS lesions are anaerobic, living in the absence of oxygen. Kriesel believes these bacteria may have come from the gut or skin, although the mechanism for arriving in the brain remains unclear.

Multiple sclerosis affects more than 2.3 million people worldwide, periodically shutting down communication between the brain with other parts of the body. Symptoms range from numbness and tingling in the appendages to blindness and paralysis. Treatments are limited by the medical community’s inability to predict the progress, severity, and symptoms of the disease.

Kriesel notes that the results of the study may be limited by medications taken by both MS and epilepsy patients, which could have altered the composition of microbial communities in the lesion samples.

“We cannot yet say that any of these microbes are causative of disease, but it is an interesting development and provides a new way to examine this disease,” said Kriesel. “I believe the list of microbes will help us understand where to go next with this approach.”

To learn more about this work, visit Dr. Kriesel’s blog: Cracking the MS Code.

###

Kriesel was joined in the study by Preetida Bhetariya, Zheng-Ming Wang, David Renner, Cheryl Palmer, and Kael Fischer from U of U Health. The work was supported by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.