Author: Mick Jurynec

Millions of people worldwide deal with osteoarthritis, a debilitating and painful disease where the protective cartilage capping the bones slowly wears away over time due to abnormal remodeling of the tissue that make up the joint. Researchers at University of Utah Health are using zebrafish to determine the role of one particular gene in the onset and progression of this disease. Their results are published in the April issue of the journal Human Molecular Genetics.

Tim Beals, MD, associate professor in Orthopaedics at U of U Health, brought an interesting family history to the attention of his colleague Mick Jurynec, PhD, assistant research professor in Orthopaedics at U of U Health. Several members of this family experienced early onset osteoarthritis in the big toe. While this type of osteoarthritis is common in older people, it is rare in people in their 20s or 30s.

“Arthritis in the big toe is incredibly painful,” Jurynec said. “It makes it very hard forpatients to walk.”At this time, few options are available for patients with osteoarthritis beyond treating the pain or, when possible, replacing a joint.

Jurynec and his team sequenced the genome of the family members to decipher the genetics driving this disease. They found the affected members had a rare mutation in the Receptor Interacting Protein Kinase 2 (RIPK2) gene.

RIPK2 is central to the body’s innate immune response. It plays an important role in fighting infection by initiating inflammation. Previous studies showed a link between this gene and arthritis in mouse studies. By removing the gene, the mice were protected from the ravages of the disease.

In this study, the researchers hypothesized that the mutation may cause the gene to be hyperactive and result in an increased or prolonged inflammatory response. For example, if you stub you toe and stimulate the inflammatory response, RIPK2 is activated and the mutated gene either produces more inflammatory cytokines or stays active when it should be shut down. Over time, the continued inflammation destroys the joint.

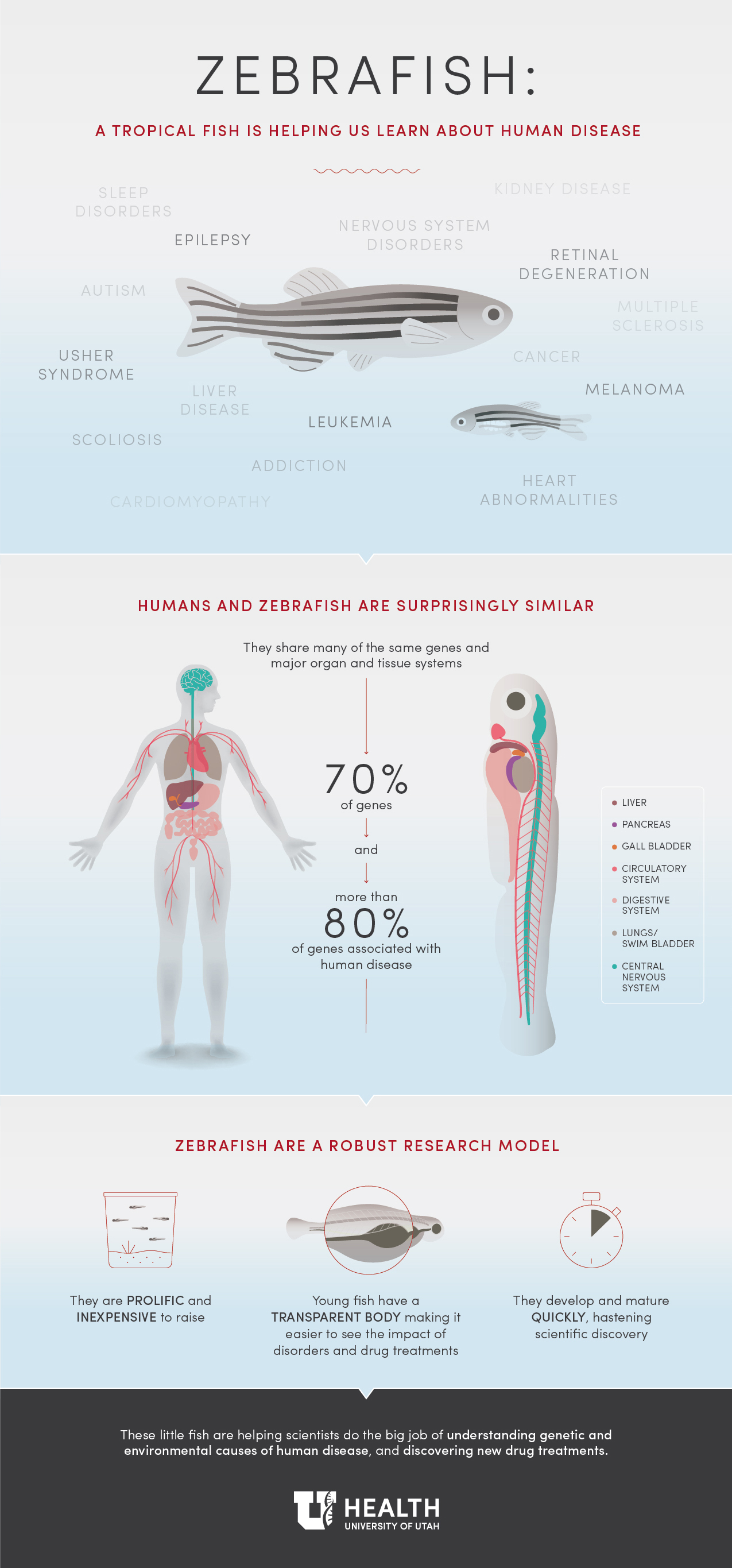

Jurynec turned to zebrafish to understand the link between the mutation in this gene and how it affects the inflammatory response.

“One of the limiting factors of human genetic studies is confirming what a gene mutation does,” explained Jurynec. “We use loss- and gain-of-function experiments in zebrafish as a rapid way to determine how the mutation affects protein function.”

These studies confirmed that the mutation identified in affected individuals augments the inflammatory response.

“Inflammation is a key part of osteoarthritis but it is commonly considered something that happens at the end of the disease,” Jurynec said. “Our studies are interesting, because it identifies inflammation as a key risk factor for osteoarthritis.”

With a better understanding of the role of the RIPK2 gene mutation on disease, Jurynec’s lab is now directing their focus to mouse studies, which he says is a more appropriate system for studying how inflammation affects the joint.

Jurynec concedes that this endeavor is still in its infancy. More work is necessary to determine if other families with big toe osteoarthritis have mutations in the RIPK2 pathway, and mouse studies will be necessary to understand how this gene exacerbates osteoarthritis and other inflammatory diseases.

These findings are a first step. Genetic insight into osteoarthritis in the big toe could help researchers better understand how other forms of the disease begin or progress. It also offers hope for the development of new therapeutic interventions.

Jurynec and Beals were joined in this study by Allen Sawitzke, Michael Redd, Jeff Stevens, Brith Otterud, Mark Leppert, and David Grunwald of U of U Health. The study was funded by the Utah Genome Project and the National Institutes of Health.