Author: Olga Baker

A healthy person produces three to six cups of saliva a day. Those with Sjögren’s syndrome, an autoimmune disease, produce far less. Researchers at the University of Utah Health identified an important molecular mechanism that may influence the progression of this disease in mice. Their results are published in the April issue of American Journal of Pathology.

“Your life without saliva would be terrible,” begins Olga Baker, DDS, PhD, associate professor in Dentistry at U of U Health.

“Your life without saliva would be terrible,” begins Olga Baker, DDS, PhD, associate professor in Dentistry at U of U Health.

Saliva is essential. It begins the digestion process for dietary starches and fats, lubricates the throat for swallowing, and protects teeth from decay.

“Imagine the worst dry mouth you had when you were sick and now make it ten-times worse,” said Ching-Shuen Wang, PhD, a bioengineer and postdoctoral fellow in Dentistry at U of U Health. “This is one of the most under diagnosed diseases because people don’t realize that they have it.”

More than four million Americans are affected by Sjögren’s syndrome, which affects the moisture-secreting glands of the eyes and mouth. It is commonly diagnosed in post-menopausal women or as a secondary autoimmune condition co-occurring with diseases of the connective tissues, such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or scleroderma.

At this time, the medical community does not know the cause of this syndrome, there is no cure, and treatments are limited to managing the symptoms.>

“As a dentist working with patients with Sjögren’s syndrome, I saw their immense suffering and devoted my life to research this condition,” Baker said. “We are going back to the beginning to study the molecular mechanisms behind the disease so we can design new therapies.”

Previous work showed that a gene called ALX/FPR2, which regulates antibody production in both humans and mice, reduces salivary gland inflammation while promoting tissue repair. Baker and Wang were curious if it also played a role in Sjögren’s syndrome.

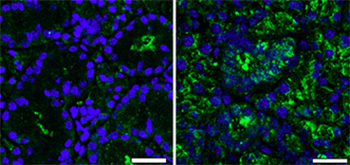

Their work shows that 12-week old female mice lacking ALX/FPR2 produced less saliva and were more susceptible to salivary gland inflammation than their wild type counterparts. The amount of inflammation was exacerbated by age.

Next the researchers compared saliva reduction to antibodies levels in the salivary gland cells of the mice. They found that the female knock-out mice with inflamed salivary cells contained higher concentration of antibodies and genes and proteins that regulate B cells, a white blood cell responsible for producing antibodies.

While it remains unclear how ALX/FPR2 regulates immune cells, it is involved in the inflammation that slowly cripples the salivary gland, preventing it from functioning properly. What the researchers did not anticipate was the gender differentiation of the results.

“All of the female knock-out mice had higher levels of B cells [than males did], which is critical for starting the disease,” Baker said.

In the future, Baker and Wang plan to explore the role of hormones in disease progression to explain the sexual differences in the results. In addition, they want to examine how the disease manifests in people.