Author: Karen Gunning

As the opioid epidemic continues to batter communities across the country, primary care physicians are on the front lines, providing about half of all opioid prescriptions in the United States. Managing care for patients with chronic pain is complicated as practitioners navigate the need to alleviate pain while keeping powerful medications off the streets. Nicholas Cox and colleagues at University of Utah Health led a pilot study to evaluate whether integrating a pharmacist into the primary care team could address the problem. They evaluated how practitioners adjusted their therapeutic approach with these at-risk patients if they were provided patient-specific recommendations from a pharmacist. The results were published in The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine in January 2018.

Previous studies showed that integrating a pharmacist into team-based care improved outcomes for diabetes patients and reduced medical cost. Using this previous success as a model, Cox developed a four-month pilot study to evaluate ways to improve care at a family medicine clinic while responsibly managing opioids and supportive non-opioid pain prescriptions.

“This is a way to clear the muddy water,” said Cox, PharmD, clinical pharmacist at U of U Health. “A pharmacist is uniquely trained to provide recommendations about these medications.”

In the study, a pharmacist reviewed the electronic health records for patients prescribed more than 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day prior to a scheduled visit. After reviewing the file, the pharmacist provided a series of recommendations for the practitioner that ranged from strategies to taper opioid or other pain medications to suggesting a referral to a pain specialist.

“It is not an overly burdensome for a pharmacist to complete these reviews,” said Cox. On average, the task took about 30 minutes per patient in the study.

Medical practitioners weighed the recommendations against their patients’ needs. They commonly implemented plans to manage multiple pain and opioid doses and offered outpatient naloxone prescriptions.

“The relatively short duration of the study is a limitation, but within the four months we saw pretty substantial impacts,” Cox said.

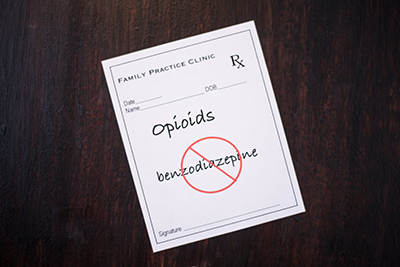

The number of opioid pills prescribed per month decreased by 14 percent. The dual prescription of opioids and Benzodiazepine, a sedative commonly prescribed for anxiety, also decreased from 37 to 31 percent.

Despite the brevity of the study, practitioners found effective ways to taper these medications and counsel reluctant patients on changes to their pain management program. Of the 45 patients who met the criteria for this study, 27 had return visits and did not show a statistically significant change in their pain scores despite changing their pain management program.

The authors note that the outcomes from this study may have been influenced by practitioner awareness of the severity of the opioid epidemic, as well as exclusion of eligible patients from the study who use opioids for purposes other than cancer or palliative care.

“Everyone knows there is an opioid problem, and there is no one-size-fits all approach,” Cox said. “We are excited to have a way to collaborate with physicians to help patients.”

This pilot study has been expanded to all of the U of U Health clinics. This project was supported by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Research and Education Foundation.