Author: Amnon Schlegel

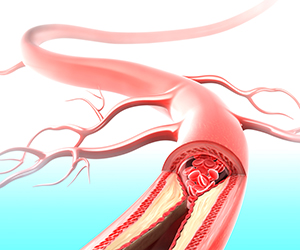

Cholesterol and triglycerides are fats carried in the bloodstream that can slowly accumulate as a plaque that coats artery walls. As the arteries narrow and harden, blood flow is restricted, robbing the body of oxygen and contributing to the incidence of heart attack and stroke. Researchers at the University of Utah Health are turning their attention to a seemingly unlikely perpetrator, the intestine, to understand its role in controlling the concentration and type of fat deposited into the bloodstream.

“The intestine acts like a pace setter for how quickly dietary fats get into circulation,” said senior author Amnon Schlegel, MD, PhD, an associate professor in Internal Medicine, Biochemistry, and Nutrition & Integrative Physiology at U of U Health.

Think of it this way. The fat from a particularly tasty donut is not dumped directly into the bloodstream. The intestine controls the release of the fat, which are then delivered to the tissues for use or storage after a meal. Researchers have known for decades that the intestine played a role in the storage of fat, but the reasons for this storage have just started to be understood.

Schlegel and his team focused on the Liver X receptors (Lxra), a protein that bind to the waste products of cholesterol. When Lxra binds to these waste products, it can turn on genes that activates the body’s garbage disposal system to eliminate excess cholesterol.

“The new thing we found in this study is that the intestinal genes turned on by the Lxra receptor put a break on the delivery of dietary fats to the bloodstream,” said Schlegel.

In effect, the Lxra receptor holds the dietary fats in temporary storage in the intestine, where it is burned and cleared from the body.

Schlegel and his research team clarified the role of the Lxra receptor using a zebrafish animal model.

The researchers examined how the receptor functioned in wildtype fish and two Lxra extremes — fish that overexpressed the Lxra receptors and fish that lacked the Lxra receptor. Fish strains that overexpressed the Lxra receptors in the intestine had reduced transport of fats to the bloodstream and were protected from high-fat accumulation in blood. In fact, these zebrafish were protected from high-fat accumulation in blood, even after eating a special high cholesterol fishmeal. Conversely, the zebrafish lacking the Lxra receptor showed an increase rate of fat transport to the bloodstream after every meal, and more fat accumulated in the blood and liver between meals.

One unexpected outcome of this study was the difference in how the receptor transported dietary fats in adult male and female zebrafish. Regardless of how the Lxra receptor functioned, the female fish cleared fat from the blood more effectively than their male counterparts. Schlegel and his team want to explore this finding in future work.

The research team hopes a better understanding of the role of the intestine in the absorption, storage, and production of fats could result in new drug therapies to treat a myriad of cardiovascular disorders.

This work, conducted along with Tibiábin Benitez-Santan and Sarah E. Hugo at the University of Utah Molecular Medicine program, was published in the May issue of Frontiers in Physiology.