Eight seconds. It’s the length of time that a rodeo cowboy must stay atop a bucking bull to earn a score. Eight ticks on the clock is also how long it takes, on average, before your doctor cuts you off in the middle of your story about where it hurts and when it started. The story you’ve been practicing under your breath in the car on your way to an appointment that’s been circled on your calendar for six weeks.

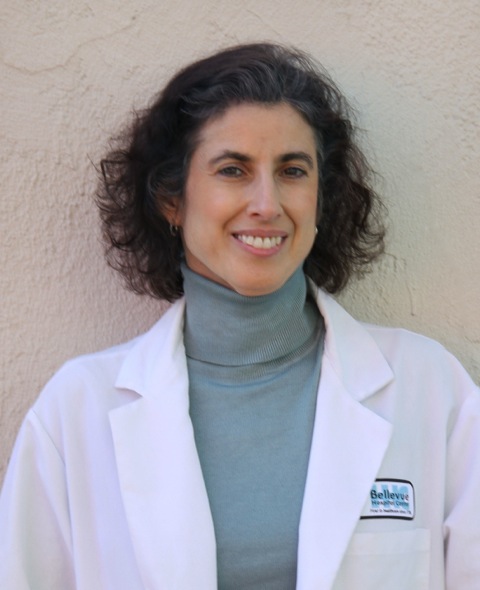

Physician and author Danielle Ofri’s advice to fellow health care providers when it comes to patient visits?

“Just shut up for the first minute,” said the author of the new book What Patients Say, What Doctors Hear. “Don’t say a word. Just listen and focus intently. Let the patient talk.”

It’s not just about being polite — it’s about effective medicine, said Ofri, who recently visited the University of Utah to deliver the H.A. & Edna Benning Society Public Lecture in Medicine. As she puts it, “The patient’s story is the primary data.” Miss a clue there and it could be lost forever, especially if it’s not the type of thing to show up on a CAT scan or X-ray.

“We end up directing the conversation,” Ofri said, “and we never get back to the patient’s second complaint, which may be the important one.”

Doctors aren’t intending to be rude, Ofri said. They see themselves as detectives who must figure out each case as quickly and efficiently as possible, because six more patients are waiting just outside the door, each with riddles of their own. Add to their workload the 10 voice messages awaiting response — the doctor will try to get to those on her lunch break — and it’s easy to see why, as Ofri says, providers are often listening “with half an ear at best.”

Technology could be exacerbating the problem. Take, for example, the burden of filling out the electronic medical record (EMR). It’s distracting for doctors to have to click all the required boxes and fields on their computer screen and simultaneously try to listen to the patient, says Ofri.

A lot can be missed when a doctor isn’t fully engaged. Ofri offered the example of a young women who came to see her for a very minor scalp condition and aches in her legs and arms. “I examined her, said ‘It’s just the aches and pains of life — you’re fine,’ said goodbye and escorted her to the door,” Ofri remembered. “I go back to writing, and she’s out in the hallway, hand still on the door knob.”

That’s when the patient revealed what was really going on.

“Doctor, do you think maybe these spots hurt because that’s where my husband shot me with a dart gun?” she asked.

Ofri had missed the signs of domestic violence.

“Had she not been courageous enough to hold onto the door knob and say that, I would’ve been like dozens of other doctors who would’ve passed her along,” Ofri said. “I wasn’t listening hard enough. If someone comes in with disparate symptoms that don’t make sense, before you say ‘Oh, it’s nothing,’ you need to make sure there aren’t other things, such as depression, abuse, violence, eating disorders and rare illness.”

But if you let patients talk, won’t they just . . . keep talking? And won’t that drain valuable time from a doctor’s already packed day? Ofri wanted to know, so she tried an informal experiment, allowing her patients to speak until they were finished.

“Most [of my patients spoke] for less than two minutes, and even my most loquacious patient with a million complaints spoke for no longer than four minutes,” Ofri said. “And you know what she said to me afterwards? ‘I feel so much better getting it all out.’ I was shocked. I’d never had a patient actually say that.”

So, what’s a busy doctor to do? In addition to listening intently to the patient for the first 90 seconds or so, Ofri recommends acknowledging the EMR.

“You can say ‘I don’t want to miss what you have to say – do you mind if I write while you speak so I can get it all down?’” Ofri said. “You’re acknowledging the necessary evil of the computer but not simply staring at the computer and not connecting at all.”

When it comes to communicating with her patients, Ofri tries to make good use of the physical exam. “That’s when we’re just two human beings, touching and talking with no screen between us,” Ofri said. “I find often that that’s when patients will really tell me what’s on their mind.”

Ofri’s advice to patients? Ask for time to talk. Surely, if a cowboy can stay aboard a 2,000-pound, combative bovine for eight seconds, a doctor can listen to a patient for at least that long. Right?

“If your doctor completely cuts you off, you can say ‘You know, just give me one minute and let me get my story out, and then I’ll let you say what you have to say.’ And if they don’t listen, you can say ‘Hey, if you give me this minute to speak, you’ll probably make a more accurate diagnosis, probably make fewer errors, and I’m less likely to sue you’ — which I think is true.”

Now, that’s clear communication.