There have been many stories in the news recently about legislation designed to end the work of equity, diversity, and inclusion in higher education. I participate in multiple national leadership teams where these laws are regularly discussed and where many people have expressed to me the trauma they’ve experienced as a result of legislation (and constant threat of new legislation) and the rhetoric surrounding these policies.

I’m fortunate to work in an institution where the values of equity, diversity, and inclusion are embedded in our daily decisions and actions. Our leaders have been remarkable in their commitment to this work and in addressing the hurt many of our employees feel. Nevertheless, I too have been affected by the body politic, and today I will share one tool that has helped me. It is a book called “The Anatomy of Peace,” by the Arbinger Institute—and I have to credit my wife, Moraima Rodríguez, MA, for first sharing it with me.

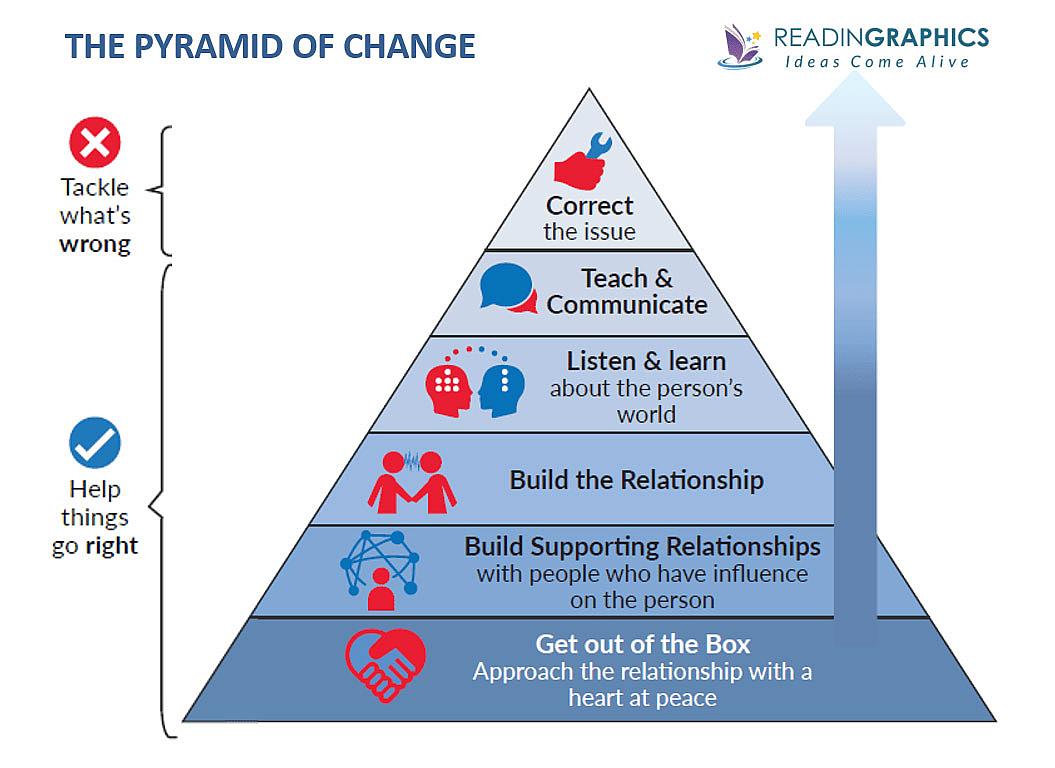

This book was published after the September 11th attacks on the United States and has been instrumental in helping business leaders find ways to resolve conflicts. The central theme of the book is the notion that we can only resolve conflict and affect change if we have a heart at peace. The authors maintain that the only way to have a heart at peace is to recognize the humanity of those who oppose you and stop seeing people as objects in our way, obstacles to be removed. The book also goes into detail about how we, as humans, tend to engage in the exact behavior that fuels conflict, even when we profess that we are trying to end it. The authors call that “collusion.” A great summary of the ideas in the book is reproduced here:

The “box” (at the bottom of the pyramid above) is the space where all of us exist when our hearts are not at peace, and we see others as objects and not people. But if we are to change how we deal with conflict and shift behaviors in others, we need to spend most of our time in this space. It is important to recognize that the book does not address how to go about changing the mindset of others; it only talks about how each of us can change ourselves, and how that can lead to changed behaviors, even if the person never agrees with our point of view.

I’ve reflected on the book’s message a great deal since finishing it—and it’s become clear to me that when I feel like there is a conflict I’m facing, there is almost always a way out. Instead of labeling those individuals who oppose my worldview, my research, or my job by their behaviors (bully, bigot, racist, etc.), I need to think of them as people, siblings in the human family who have children or pets or relatives with cancer.

I’ll admit, when I first tried this approach, it felt a little trite and frankly too easy to be true. But then, when I started talking about the conflict with others and thinking about the person, I noticed a difference in my disposition. I imagined those who opposed me having to walk their dog when they were tired, or caring for a sick parent, and the negative emotions vanished. Moreover, I was able to think clearly about the anger and the hurt—and then move toward a solution.

Recently, Tim Shriver, an Impact Scholar at the University of Utah, addressed our graduating class. He spoke of the dignity index and how the simple task of recognizing the dignity of others can make conflict less of an emotional chore and more of a solutions-oriented experience. His talk reminded me of my experience with “The Anatomy of Peace.” I hope all of us can use this information to address conflict in a positive way, showing our friends and colleagues that we can use differences of opinion to get to a better place.

To receive stories like this directly in your inbox, please consider subscribing to the MEDiversity Newsletter. The monthly newsletter, sent every first Tuesday of the month, will help you stay in the loop with all things related to health equity, diversity, and inclusion from University of Utah Health Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (UHEDI).